My friend Jack Shafer phoned this morning to warn me that nobody knows anymore who Sammy Glick is. In my latest New Republic column I express disappointment that J.D. Vance, author of Hillbilly Elegy, has turned into “an Appalachian Sammy Glick,” a kicker that, in fact, my young-ish editor there made a point of admiring when he sent the readback. But Shafer appears mostly to be correct. Jonah Blank, a friend whom I’ve always considered more learned than myself, confessed on Twitter that “I had to Google ‘Sammy Glick.’”

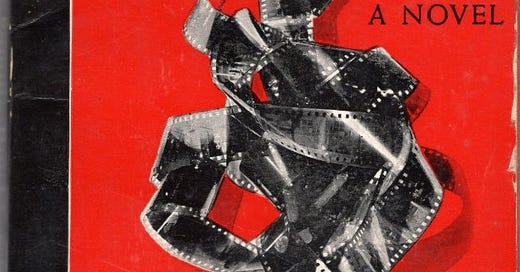

Sammy Glick, kids, is the villain of Budd Schulberg’s 1941 novel What Makes Sammy Run? Sammy is one of the great American literary archetypes—a smart, obsequious young guy on the make, constantly in motion, “agile without grace,” and utterly duplicitous when you turn your back on him. He’s a sort of American Julien Sorel, only nastier and more personally obnoxious.

Schulberg’s writing has proved enduring, mostly through his screenplays and screen adaptations of his novels and short stories. What Makes Sammy Run? was made into a short-lived Broadway musical but never, Shafer pointed out to me, a movie, which may account for Sammy’s short shelf life. The novel itself is not something I would urge anyone to hunt down and read; it gets bogged down in tedious detail about the politics of Hollywood unions (Sammy is a newspaper copyboy turned screenwriter turned producer). The only thing that’s really great about What Makes Sammy Run? is the we’ve-all-known-guys-like-this Sammyness of Sammy.

A possible good reason society has forgotten Sammy Glick is his uncomfortable proximity to the anti-Semitic stereotype of the pushy little Jew. It probably isn’t an accident that variations on this character tend to attach themselves to groups whose incursion on the social scene is resented by the majority. Sammy begat Eve in All About Eve and Tracy Flick in Election, and while I’d defend all three as deliciously drawn antiheroes, it probably isn’t a coincidence that Sammy was Jewish when anti-Semitism was still mainstream (though not so much in Hollywood, where the book is set) and that Eve and Tracy were women when misogyny was a not-atypical response to women clamoring for their fair share.

The mistake the majority culture makes when it condemns duplicitous ambitious strivers lies in equating the ambition of excluded individuals, which is good, with duplicity, which is bad. That is bigotry, a very old story. Sammy and Eve and Tracy are great characters because they complicate this moral lesson by being the very thing that good people are on guard not to believe them to be. They are, in the great Yiddish expression, a shanda fur die goyim, an example the enemy will cite to conclude, falsely, that the stereotype is true, which it isn’t. (Possibly the greatest literary use of this theme in the modern era is Philip Roth’s short story, “Defender of the Faith.”)

Another reason Sammy Glick may have vanished from the scene is that, starting in the late 1970s, American culture started making the opposite mistake—looking at duplicitous ambitious strivers and pretending that the duplicity wasn’t there, or was entirely justifiable. The best-selling Looking Out For Number One gave Americans permission to stab your buddy in the back. He’d do it to you! Gordon Gekko pronounced greed to be good.

The whole thing drove Schulberg batty. “I'm astonished and somewhat alarmed to find that the book is now popular book in a different way,” he told the New York Times in 1978 about the appeal of What Makes Sammy Run? to a new generation of arrivistes. “Sammy's behavior then seemed more scandalous. It's incredible to me — the change in our social morality. I find it a sad commentary that a character I thought of as so completely an antihero becomes, later on in the same century, a model for what I consider antisocial behavior.” A few years later, young Reagan Republicans were actually approaching Schulberg to tell him they wanted to be just like Sammy Glick.

Anyway. The point of my New Republic column is that I admire J.D. Vance the striver, as described compellingly in Hillbilly Elegy. I was even moved by the movie. What I don’t like is J.D. the phony, who’s gone from saying Donald Trump is “leading the white working class to a very dark place” to racing to catch up to follow Trump into that dark place. The old Vance was someone to admire. The new Vance is not.

Love this article, Tim! BTW, I am also on substack - rickgeissal.

Reminds me of when I got a book autographed by the great Calvin Trillin. When I told him to spell my first name like Merle Oberon, he took a beat, then looked up at me and said, "I don't think you're going to be able to use that much longer."