Identity politics used to be about affinity. “Gay is good,” said the burgeoning gay-rights movement. “Black is beautiful,” said civil rights groups after the most obvious forms of segregation were eliminated. “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s real Jewish Rye,” said the ad firm Doyle Dane Berbach, whose many achievements within the profession included ending its systematic discrimination against Jews.1 Today, for better or worse, identity politics is less about how terrific I am than about how blind you are not to recognize that, with a vocabulary (micro-aggressions, intersectionality, etc.) not of affinity but aversion.

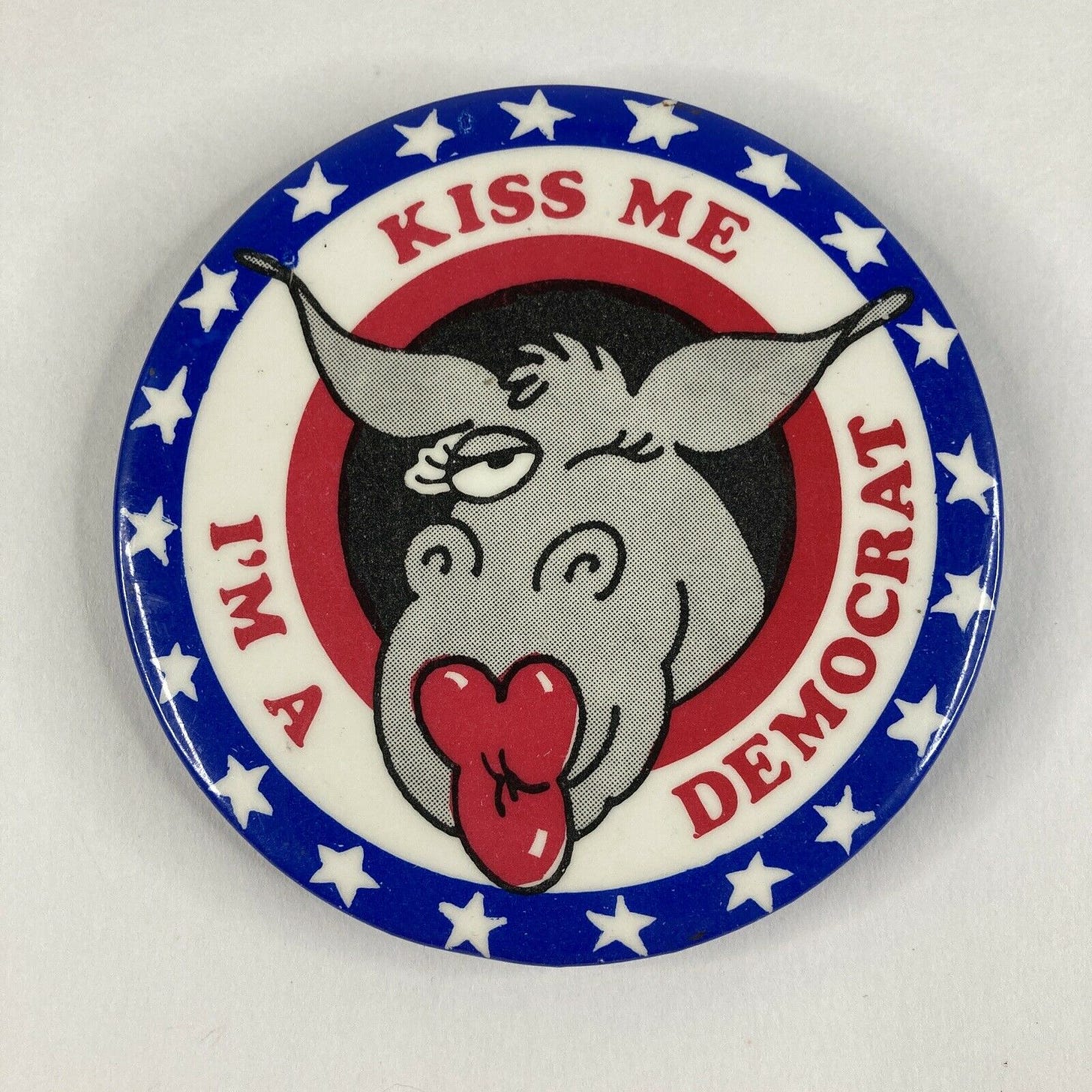

Party politics has followed the same trajectory. Democrats used to wear t-shirts that said, “Kiss Me, I’m A Democrat” and sing “Happy Days Are Here Again,” even when they self-evidently weren’t, like during the Great Depression. That a party as ideologically divided as the Democratic party during the first half of the 20th century could maintain sunny bonds of affinity seems, in retrospect, a kind of miracle. It wasn’t entirely for the good (most notoriously, it barred for many years any progress on civil rights), but it was successful electorally. Then came the Great Society civil rights laws, the Vietnam War, and Watergate, and the whole thing blew to smithereens.

Ronald Reagan was a terrible president, but give him credit for being the last president to maintain an unforced sunny demeanor. That this reflected the early stages of Alzheimer’s is a possibility we can’t rule out, but you never got the sense that he resented the other side. Possessing the soul of a country club Republican, he seemed only dimly aware that Democrats and their constituencies even existed.

Even then, though, the politics of aversion were coming to the fore. Republicans babbled endlessly about the liberal wreckage of the 1960s. Democrats chanted, “Ronald Reagan, he’s no good/ Send him back to Hollywood.” Bill Clinton got himself elected pointing out that George H.W. Bush had wrecked the economy. Barack Obama got himself elected pointing out that George W. Bush had wrecked the economy and started two endless wars in the Middle East. Both of them made “Hope” a central theme in their campaigns, but Hope mostly meant relief from disastrous Republican stewardship.

In the 1960s Democrats were arguably better than Republicans at practicing the politics of aversion, but they targeted it less efficiently, killing off the presidency of Democrat Lyndon Johnson and inadvertently ushering in the presidency of Republican Richard Nixon. That’s what happens when you elevate principle over partisan interest. Republicans never made that mistake, and by the 1990s they were the obvious champions at loathing the other side. The GOP had the additional advantage that as they moved rightward, the imperatives of governance mattered less and less to them. By the time Donald Trump came along, the GOP didn’t even want particularly to start any wars (the silver lining to the dark cloud of Trump’s four years in office). They were too absorbed with fighting the enemy at home.

This history explains why President Joe Biden, a capable chief executive with a strong record, is now going on the attack against a GOP held captive by former President Donald Trump and his assorted pathologies. That is the subject of my latest New Republic piece. You can read it here.

My father tells the story of applying in the early 1950s for a job at an advertising firm. The person interviewing him, observing that he didn’t look particularly gentile, fished around by asking about his ancestors’ nationality, the name of his wife, etc. None of this information, as it happened, furnished helpful clues, but his application was rejected. DDB demolished that world of polite anti-semitism.