He grew up on University Avenue in the Bronx, graduating from the then-brand new Bronx High School of Science in 1942, where he was valedictorian, or anyway speaker at graduation; he later insisted on making clear he did not have the highest grade-point average. In 1948 he graduated from New York University, where he majored in English. In between he served in the Army Air Corps. He was struggling to learn how to fly a plane at Tyndall Field in Panama City, Florida, when World War II ended. On graduating from NYU he borrowed his father's car and drove north through New England, looking for a radio station that might want a disc jockey with a great radio voice and a passion for swing music. He found one in Waterbury, Connecticut, "Brass City," where he hosted a program called “Noah’s Lark.” In his spare time he joined an amateur theater troupe and met my mother. They married in 1950. Both lived to celebrate their 70th wedding anniversary.

Dad wanted to be a playwright. While working in Waterbury he had several radio plays broadcast nationally, and after he sold a script for a TV play to the Kraft Television Theater (starring a then-unknown Jack Lemmon) he and my mother moved back to NYC with my older brother, Peter; my sister Patsy was born not long after. Unfortunately, the gold rush he expected did not materialize; he never managed to sell another TV script. Instead, he went to work for "Winky Dink and You," an animated children's TV show that put its protagonist (voiced by Mae Questel, who had also voiced Betty Boop) in all sorts of fixes that required children to draw, with a grease pencil, bridges and other rescue devices on an acetate sheet affixed to the TV screen that maybe Mom and Dad bought, or maybe they didn't, in which case the kids vandalized the TV screen, to Mom and Dad's obvious delight. On one episode my dad was drafted to appear in a gorilla suit. The show was cancelled in 1957 due to health worries about encouraging kids to get too close to their TV screens, given concerns (later discovered to be unfounded) about x-rays emanating from cathode tubes.

"Winky Dink" was produced by Jack Barry and Dan Enright, who also produced TV quiz shows, including “21,” where Charles Van Doren’s defeat of Herb Stempel landed Van Doren on the cover of Time. From “Winky Dink” Dad was promoted to producer for various Barry-Enright quizzes, including "21,” and eventually he became “21”’s executive producer. That situated him smack in the middle of the quiz show scandals, because just about all these shows, and most memorably “21,” turned out to be fixed. There was a grand jury investigation (inconclusive) and, famously, congressional hearings, at neither of which, weirdly, Dad was called to testify. He was always a little puzzled as to why not. I think Dad may be the last figure in that strange episode to pass on, though many of them lived to an advanced age. In 1992 PBS aired an excellent documentary that Dad declined to participate in but thought quite good. (He also declined to participate in my friend Jeff Kisseloff’s very good oral history of the early days of television, The Box.) Dad was less enamored of Quiz Show, the 1994 film, based on a script by my college acquaintance Paul Attanasio, even though Dad was not himself portrayed in the film. I think Redford and Attanasio did a fine job, but then of course I wasn’t there. I was born while the events in the film were taking place.

Dad was exiled from TV. He’d only just purchased his first house, in New Rochelle, and he must have been scared out of his wits. I know he felt humiliated and ashamed. He returned to writing scripts. He got very interested in the Sacco-Vanzetti case of the 1920s, eventually writing a play about their lawyer, The Advocate, that was produced in June 1962 at the then-quite-prestigious Bucks County Playhouse and, the following year, on Broadway.

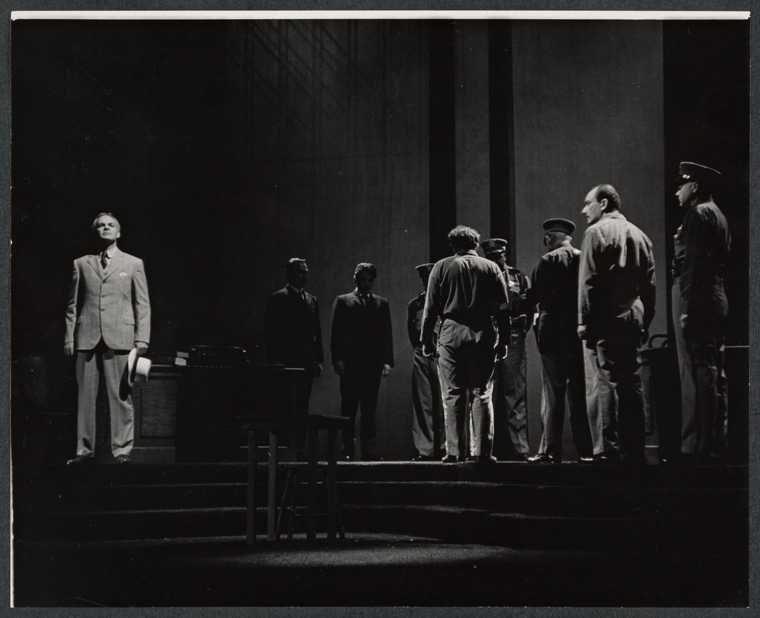

James Daly in The Advocate, October 1963

It’s always struck me that the happiest time in my father's life, in Bucks County, followed hard on the heels of the unhappiest, the very public quiz-show scandal. He struck a warm lifelong friendship with the actor Alfred Drake, who directed the play in Bucks County before handing it over for the Broadway production to Howard DaSilva; with James Daly, who played the lawyer, Curtis (a fictionalized version of William E. Thompson); and with the producers, Michael Ellis and William Hammerstein. Dad felt as though he were living a dream. "You know Sid Perelman, don't you?" Dad remembered Ellis telling him at one luncheon gathering by way of introduction. That rendered him speechless. Oh, yes, Sid & George & Dorothy & Alec Woolcott, we all lunch daily at the Algonquin, doesn’t everybody?

The Broadway production of The Advocate was more of an ordeal because Dad didn't like DaSilva and he felt he was spoiling the play, and because the play was not well-received by the critics and closed within a week or so. There was also, on opening night, a simulcast, taped earlier, broadcast in five cities outside New York. This was hailed as an historic first by the sponsoring network, Group W, and denounced as the death knell for legitimate theater by the impresario Billy Rose, quoted in Theater Arts magazine. I've never been able to get my hands on a tape or kinescope. Dad never saw it; at an advance screening of the TV version he faked a stomach ache so he could leave early. In 1969 my family went to see the original production of 1776 on Broadway. Coming out, we were all raving about Howard DaSilva’s performance as Benjamin Franklin. “He was all right,” I remember Dad grumbling reluctantly.

The play would be revived in 1976 at San Diego’s Old Globe Theater, in a production directed by Craig Noel that Dad much preferred. There was also, in 1967, a production at Riker’s Island by a group called the Theater for the Forgotten. Writing in the New York Times, J. Anthony Lukas called it “the first time professional actors and prisoners had combined efforts in a theatrical production.” That sounds to me like a stretch, prisons and the theater both going back an awfully long way. At any rate, this chronicle of injustice, Lukas could report, went down very well with the Rikers inmates:

The audience … clearly did sympathize with the prisoners. They cheered when Sacco, as played by one of the group’s founders, Akila Couloumbis, spat at his guard. When Sacco and Vanzetti’s lawyer asked: “Do they have to trace their ancestry back to the God-damned Mayflower?” the prisoners cheered and laughed and one Negro boy chortled with glee, “the God-damned Mayflower!”

After his adventures on Broadway, Dad returned to TV to produce what by then had been renamed “game shows,” working for the leading production company, Goodson-Todman. (The lame gimmick at the heart of “Jeopardy,” that you’re furnishing not answers but questions yielding the answers given, was an attempt to distinguish it from a “quiz show.”) Dad’s credits included "Concentration" and "The Match Game." On the side Dad wrote a TV special, a musical salute to George Gershwin, one of his heroes. I think William Hammerstein arranged it. The program included a performance of "Rhapsody In Blue" by Andre Previn and the NBC Orchestra. "They'd better get their act together," Dad remembered Previn grumbling. "Lenny's conducting them next week and they aren't ready." Once again, Dad was rendered speechless. Oh, yes, mustn’t disappoint Lenny, he’s a terror with a slow strings section, we all know that.

In 1969 Dad struck out on his own, creating his own game-show production company and opening a small office on Madison Ave. There were no takers, and later Dad would recall it as a year spent staring at the backwards logo

HAON TREBOR

SNOITCUDORP

through the beveled glass of his office front door. His main problem was that the game-show business had chosen that moment to move west to Los Angeles. In the spring of 1970 Dad took a job there with Filmways, which among other ventures was the producer of "The Movie Game," and we followed, settling in Trousdale, a 1950s midcentury-modern nightmare built on the hills that had been part of the ranch behind Ned Doheney's Greystone Mansion. Today it's madly fashionable among the younger set. I thought it was hideous then and I still do. Among other drawbacks, I couldn't ride my bike anywhere. A year later, in 1971, we moved to Benedict Canyon in Beverly Hills, into a Spanish-style 1920s house built too close to the road (that's why we could afford it) on a lot that somewhere along the line had been subdivided into kind of a tight fit. Still: Much better. From there, I could bicycle to school. That’s where my parents remained the rest of their lives.

Dad loved his adopted home of Los Angeles. No more commuting, no more garbage and teacher’s strikes, etc.—we left at a low point for Fun City—plus most of his friends were moving west at the same time, and he still got the New York Times every day (though not first thing in the morning, and in the early 1970s you had to pay a small fortune in L.A. just for that). His wife and kids were less thrilled with the place, but learned to adjust. The move separated Dad from his oldest and dearest friend, Jerry Brill, whom he’d met in Boy Scouts, and Jerry’s wife Jane, and from our New Rochelle neighbors, the D’Andrade family, whom we annexed to our own, and from the sprawling Bock family, whose entanglements with my family date back about a century. But there were regular visits back and forth that continued through the decades, and in L.A. we grafted on yet another family, Jay and Roz Wolpert and their kids and grandkids.

From Filmways my dad progressed to Henry Jaffe Productions, Heatter-Quigley Productions, Reg Grundy Productions and, eventually, to president of Goodson-Todman, which by then was basically a video library that sold foreign licensing rights to various shows. He retired in the 1990s and settled into a second career writing novels, starting in 1988 with All the Right Answers, a fictionalized account of the quiz-show scandals, and The Man Who Stole the Mona Lisa, a fictionalized account of a notorious art theft in the early 20th century. Late in life Dad self-published a few more novels. His Amazon page is here.

Dad was a loving husband to Marian Noah (1929-2021), father to his three kids, grandfather to ten mostly adult grandkids (including two lately acquired step grandkids he never met), and great-grandfather to seven toddlers. I hope I got those numbers right. At one family occasion I remember Dad joking that the enterprise had grown large enough to run a winery.

Dad was widely admired for his decency, a trait he acquired from his father, Mortimer (whose own father, a mailman named Samuel, was a bit of a bastard, which prompted Morty to resolve to be different, which he was). And also, apart from the quiz-show aberration, his quite scrupulous honesty, another inheritance from Morty. And for his wide-ranging curiosity (he read pretty much everything), his sense of humor, his fierce intelligence, and his quiet wisdom. He was a great lover of games, which he put to occupational use. Especially backgammon. I remember long sessions with Jerry Brill, the muffled sound of dice hitting the cork, the quiet patter between them following a particular rhythm I never heard from anyone else. In the early 1970s backgammon suddenly became fashionable and there were tournaments everywhere. At one of these, in L.A., Dad was paired with Hugh Hefner. Dad beat the pants off Hef. He didn’t brag about that, because that wasn’t his style, but it pleased him, a lot. Safe travels, Dad, and thanks for everything.

Dear Tim:

What a beautiful testament to a remarkable man. Please accept my condolences.

Mimi Harrison

What a wonderful life. Thanks, Tim, for sharing this. I’m sorry you have lost those fine people, your parents. I miss mine every day.