Memento Marian

Remembering Marian Jane Noah (1929-2021) and counting my Brood X cicada cycles.

Over a normal human lifespan a resident of the mid-Atlantic states can expect to witness five sightings of Brood X, the nation’s biggest cicada cohort, which emerges from the ground every 17 years.

I missed my first opportunity, in 1970, when I was 12. The cicadas crawled out of the ground that year shortly before my family moved from New Rochelle, N.Y., to Beverly Hills, Calif. Probably there weren’t many to see. New Rochelle is pretty far north for Brood X, which seldom extends north of New Jersey. Brood X does extend to Ohio, though, where one month earlier National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of antiwar protestors at Kent State, killing four of them.

Four days before I boarded the plane to California with my mother and sister, Brood X was making a racket in Princeton, N.J., where Bob Dylan, 29, was receiving an honorary degree from Princeton University alongside Coretta Scott King, 43, and Walter Lippmann, 81. “Dylan chatted briefly with Mrs. King, but eyewitnesses say neither Dylan or Lippmann seemed aware of the other’s presence,” reported Rolling Stone.

It’s probably just as well. Dylan behaved badly that day, throwing a tantrum in the Nassau Hall faculty room when reporters asked him a few questions, and threatening to bolt when asked to put on an academic gown. In the end he consented to wear the gown but refused to wear a mortarboard. Thinking the cicadas were locusts, Dylan wrote a song about the experience titled “Day of the Locusts,” in which he declared himself “glad to get out of there alive.” Here’s the chorus:

Yeah, the locusts sang such a sweet melody

And the locusts sang with that high whinin' trill

Yeah, the locusts sang and they was singin' for me

Singin' for me, whoa, singin' for me.

Seventeen years later, in June 1987, I was 29 and leaving brunch at my friend Gregg Easterbrook’s house in Arlington, Va., when I noticed a lot of crunchy insect carcasses underfoot. My date, Marjorie Williams, 29, explained what these were, and she may even have noted the Dylan episode, since she’d grown up in Princeton. Marjorie was working at the time as a writer on the Washington Post’s Style section, and she’d probably read this explainer by Catherine O’Neill. I was a congressional correspondent at Newsweek. This was the month when President Ronald Reagan gave his speech in West Berlin urging Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall,” which struck me as dangerous showboating at the time. I was wrong; two and a half years later, the wall fell.

When Brood X resurfaced in late spring of 2004, Marjorie and I were married. We were both 46, with two young children, Will, age 11, and Alice, age 8. The large fact in our lives was that Marjorie had stage 4 liver cancer. We spent two weeks that summer on Great Island in West Yarmouth, a place Marjorie had visited frequently as a young girl, staying in the house of a kind family friend. Marjorie died the following January, three days after her 47th birthday, which was also mine. Marjorie wrote about her illness here and in a book I published posthumously, The Woman at the Washington Zoo.

Three years after Marjorie’s death, my daughter Alice and I would return to West Yarmouth and discover that the Great Island house we remembered so fondly had been razed and replaced by a new one; the old one, our friend explained, was ravaged by termites. After lunch, Alice and I visited Edward Gorey’s house, which had been turned into a museum. I bought Alice a poster of The Gashleycrumb Tinies. “I’ve been murdering children in my books for years,” Gorey told an interviewer in 1977. (Alice’s literary taste inclines toward the macabre.)

Now Brood X is back. I’m 63 and remarried to a beautiful and vibrant woman who will take me later this month to a cocktail party where cicadas will be served as hors d’oeuvres.

The large fact in my life right now is that my mother, Marian Noah, with whom I boarded that plane to California three cicada cycles back, died last week in Beverly Hills, at 92. I flew back four days before the end, noting as I left the terminal at LAX that some of the colorful mosaics I remembered from June 1970 still lined the walls of the tunnel to the baggage claim.

My mother was in a coma when I arrived. I stroked her arm and I told her that I loved her. My sister played some music on her iPhone and held it to her ear. Mostly, though, we sat and chatted with my father, trying to keep his spirits up.

Our vigil was not as solemn as I’d expected it would be. We didn’t speak in hushed tones; indeed, because my father is losing his hearing, we mostly had to bellow to be heard over the drone of my mother’s oxygen supply. We watched Test Pilot and On the Waterfront on Turner Classic Movies. We talked about the weather. I made a big batch of my friend Mary Kay’s tarragon-smothered chicken salad. One night we ordered pizza. I told the story of a friend who, while holding vigil for a dying relative, with family members gathered around the loved one’s bed reciting tearful goodbyes, heard a sudden crash. All eyes turned to a home health care worker who had dropped to the ground, dead. It took a moment or two before anyone could absorb this information.

Now I’m back in Washington as the cicadas start to crawl out of the ground, and all I really want to do is look at photographs of my mother. I’ve been posting them at a lunatic pace on Facebook.

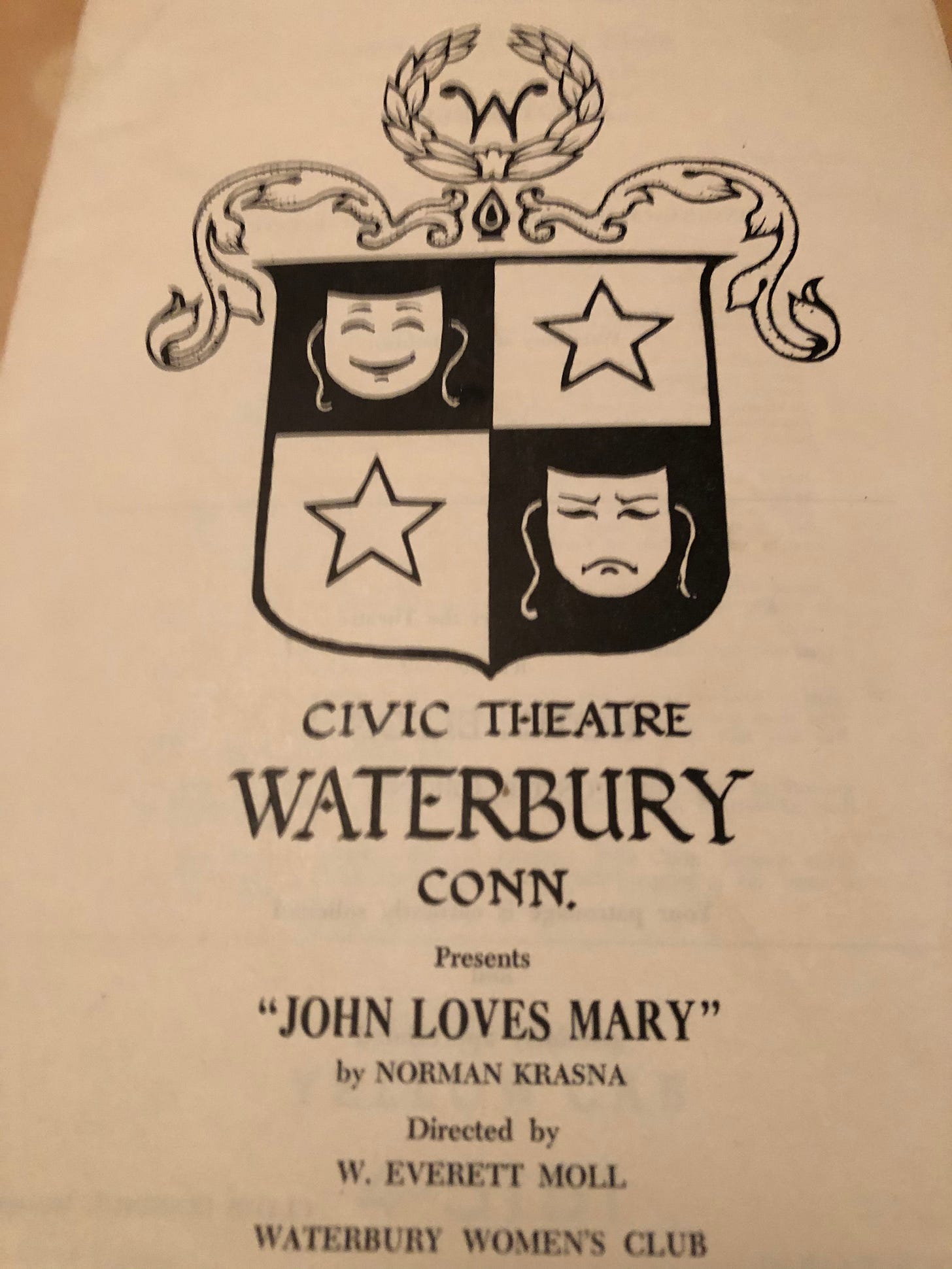

That’s Marian, above, with my son Will, now 28. She was a really great grandma, with lots of practice by the time my kids came along. She was a great mom, too—loving, funny, immensely proud of her children (she kept scrapbooks galore), and, my friends were always telling me, sort of glamorous. She met my father when they appeared together in a community theater production of John Loves Mary, a comedy about a returning GI’s love troubles that was made that same year, 1949, into a film starring Ronald Reagan and Patricia Neal. The screenplay was adapted from Norman Krasna’s stage play by Phoebe and Henry Ephron, who are remembered today chiefly as the parents of the witty essayist and filmmaker Nora Ephron.

My mother played the Patricia Neal role, Mary, sweetheart to John, who’s brought home an English war bride named Lily so that she can emigrate to the U.S. My father played John’s former Army lieutenant, Victor O’Leary, who’s enlisted to disentangle this mess before Mary finds out (and of course ends up marrying Lily).

My parents married in January 1950, three years before the Brood X emergence that preceded the one that inspired Dylan’s “Day of the Locusts.” They lived to celebrate their 71st wedding anniversary four months ago, under Covid lockdown.

If I’m lucky I’ll witness one more round of Brood X in 2038, when I’m 80. It doesn’t seem probable I’ll be around for the 2055 emergence. More likely I’ll be in the ground, at approximately the same depth as the Brood X nymphs before they emerge, mate, and die, all in a period of about six weeks. In Hermione Lee’s recent biography of Tom Stoppard she writes that Stoppard greatly admires James Saunders (1925-2004), a Beckett-inspired playwright whose Next Time I’ll Sing To You influenced (and was eclipsed by) Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. The West End production in 1962 starred a young Michael Caine. Stoppard likes to quote this passage from the play:

There lies behind everything … a certain quality which we may call grief. It’s always there beneath the surface, just behind the facade. Sometimes … you can see dimly the shape of it as you can see sometimes through the surface of an ornamental lake the outline of a carp … It bides its time, this quality … you may pretend not to notice … the name of this quality is grief.

Marian Noah, requiescat in pace.

It's true that the apple doesn't fall far from the tree. You are a lovely man.

Beautiful, dear Tim.