A Brief History of Me

Wherein your correspondent shares some family history, connects it to the G.I Bill, and considers that the same benefits were largely unavailable to Black World War II veterans and their descendants.

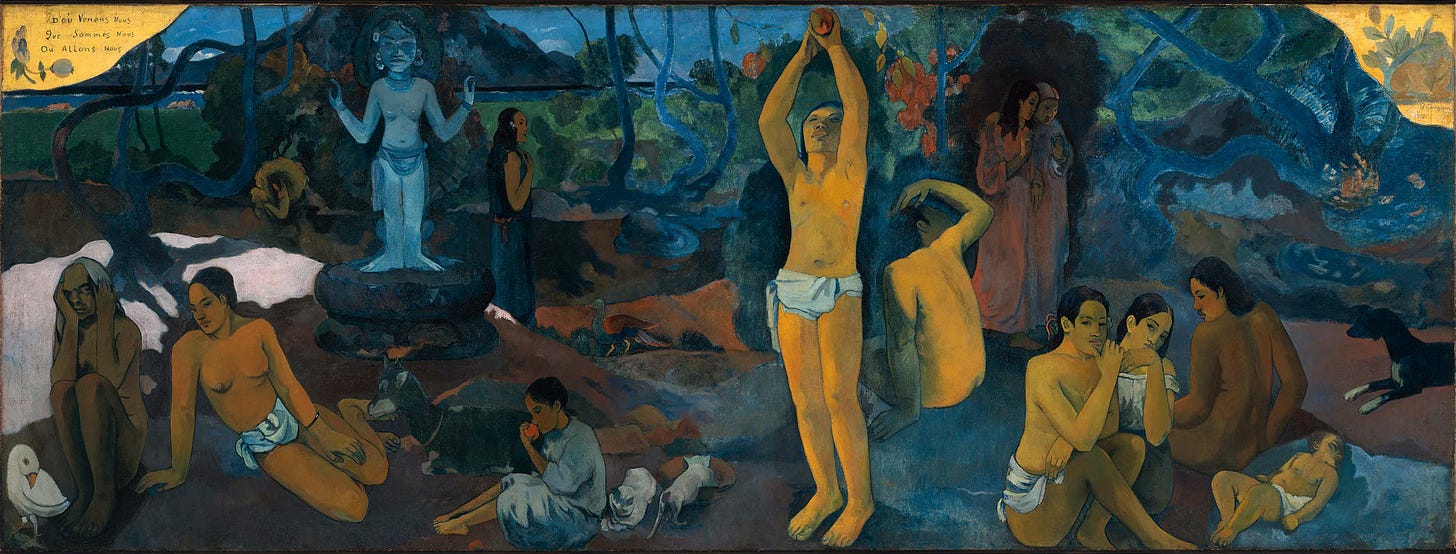

D'où venons-nous ? Que sommes-nous ? Où allons-nous? That is the title of Paul Gaugin’s 1898 masterpiece, which resides at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Gaugin began work on this painting seven years after (in the most notorious male midlife crisis in human history) Gaugin abandoned wife and children in France and hot-footed to Tahiti. Not that it was any comfort to Mme. Gaugin, but her loss was Art’s gain.

At 65, I’ve got a pretty good grasp of questions two and three: We’re human beings and we’re going to die. (I’m not particularly metaphysical.) But I confess to some puzzlement about question one. After my father passed away in June I did the stereotypical male-menopause thing and started digging into family history. I got as far back as Noah DaCosta, b. 1680 in London, 25 years after Oliver Cromwell let the Jews back into England, ending their four-century exile. The Noahs were Sephardic Jews who had to leave Portugal and Spain to escape the Inquisition and all that followed; Sephardim were either forced to convert to Catholicism (conversos) or pretended to (Marranos); the preferred term for Marranos today is “crypto-Jews” because Marrano means “swine.” Just about every Noah I could find prior to my great-great grandfather Moses Noah, who emigrated to New York in July 1863, was buried at Novo Cemetery in East London, which I visited recently with my son. But in the mid-1970s they were pretty much all dug up and dumped into a mass grave in Essex to make room for expansion of the adjacent Queen Mary University. The best my son Will and I could do was find a grave for one Benjamin Noah DaCosta, died 1879, who turned out to be my second cousin four times removed.*

There’s some evidence that Noah DaCosta was a prosperous merchant, but within a few generations the family tumbled into the proletariat. Moses, who in the United States went by Morris, was a cigar-maker; his son Samuel was a postman; and his son Mortimer worked at a glass factory. My father was the first of Moses’ descendants to go to college, at least in the direct line that leads to me, and also the first to own his own home. That’s in large part thanks to the 1944 G.I. Bill.

In my latest New Republic piece, I write about how the great opportunity for advancement that the G.I. Bill extended to the Noah family was mostly unavailable to Black World War II veterans and therefore to their descendants. We can do something about that. You can read my piece here.

*This is updated.

I enjoy reading your articles.

I wish I had had enough sense to thoroughly interrogate my oldest great aunts and uncles. Being supremely disinterested in the old people of my youth, I failed to tap this source of family tales. At some point as I grew up, I realized I had so many questions and no one left answer it. I did assign a student project to go home and questioned the oldest people in your family. Some of the kids in the class were astonished by the things that happened to their oldest family members.