You can't get a raise from a crap job

Lessons from Pew's survey on why workers are quitting in record numbers.

Johnny Paycheck, performer and coauthor of “Take This Job and Shove It” (1977).

In 1990 a self-help sage named Robert Fulghum published a best-selling book titled All I Really Need To Know I Learned in Kindergarten. I’m resistant to this philosophy because the main thing I remember from kindergarten is the assassination, two months in, of President John F. Kennedy. Getting through life has required me to know a hell of a lot more than that singularly awful fact. But I’ll give Fulghum this: Kindergarten is where I met Danny Alpert, from whom I learned most of what I know about the Crap Job Economy. Danny, who now goes by the more dignified Dan, imparted this knowledge four decades after we’d both departed Miss Hambel’s kindergarten class at the now-defunct Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School in New Rochelle, N.Y., and he probably would have been willing to tell me about it even if we didn’t share that old school tie. But we do.

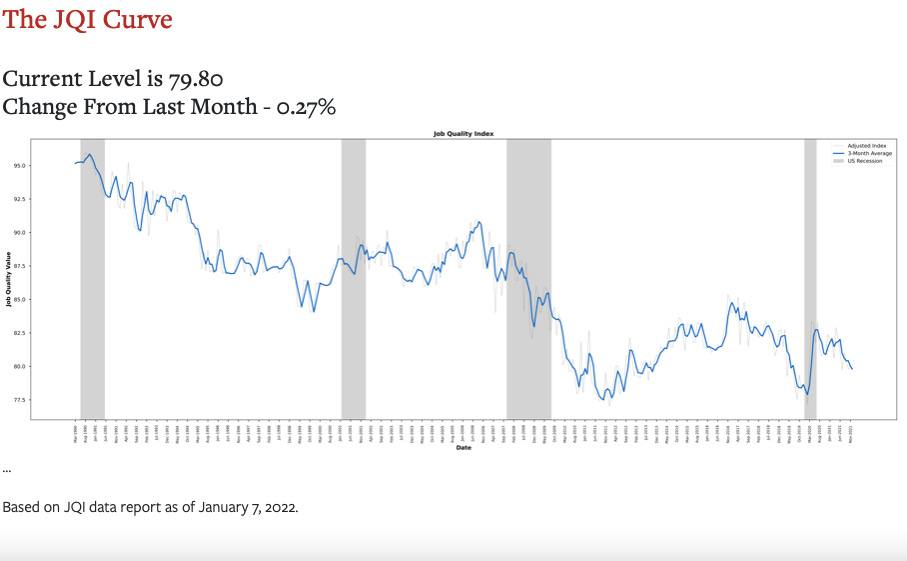

Dan, along with various academic colleagues with whom I didn’t attend kindergarten, is the creator of the Job Quality Index (JQI), which gets posted every month to put the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ job-growth numbers in some perspective. The JQI is calculated by dividing the number of good jobs (i.e., those that pay above the mean weekly wage) by the number of crap jobs (i.e., those that pay below that mean) and then making various technical adjustments. (For a fuller discussion of the methodology, click here.) The JQI has been mostly declining since the data series began in 1990. It spiked at the start of the Covid pandemic, but for a bad reason: The unemployment surge concentrated heavily at low incomes, i.e., crap jobs. Putting people with crap jobs out of work raised job quality without actually improving (indeed, worsening) the quality of workers’ lives. Now the unemployment surge has receded almost completely, and a stupendous quantity of jobs (678,000 in February) is being created every month. But they’re heavily tilted toward crap jobs. Here’s the latest JQI chart, updated to January 2022, showing a JQI of 79.80, down 0.27 from December 2021. Read it and weep:

In my latest New Republic column, I consider the results from a new Pew survey asking workers why they’ve pushed the “quits rate” to its highest-ever level and kept it there for 10 long months. Their answers, I suggest, reflect the fact that in our economy crap jobs are typically segregated from big, profitable businesses in crap-job mills: fast food franchises, staffing companies, etc. You can’t get a raise or a promotion because all the jobs in these workplaces are crap jobs. You can’t get any respect from your better-paid coworkers because those coworkers aren’t really coworkers at all; they work for an entirely different company, one that pays better benefits and likely is more scrupulous about observing labor laws.

Anyway, you can read it here, and I hope you will. They don’t teach this stuff in kindergarten, or even, I think, in business school.