Why Aren't People Remembering Trump's Spectacular Mismanagement of Covid?

We tend to forget pandemics. We mustn't forget this one.

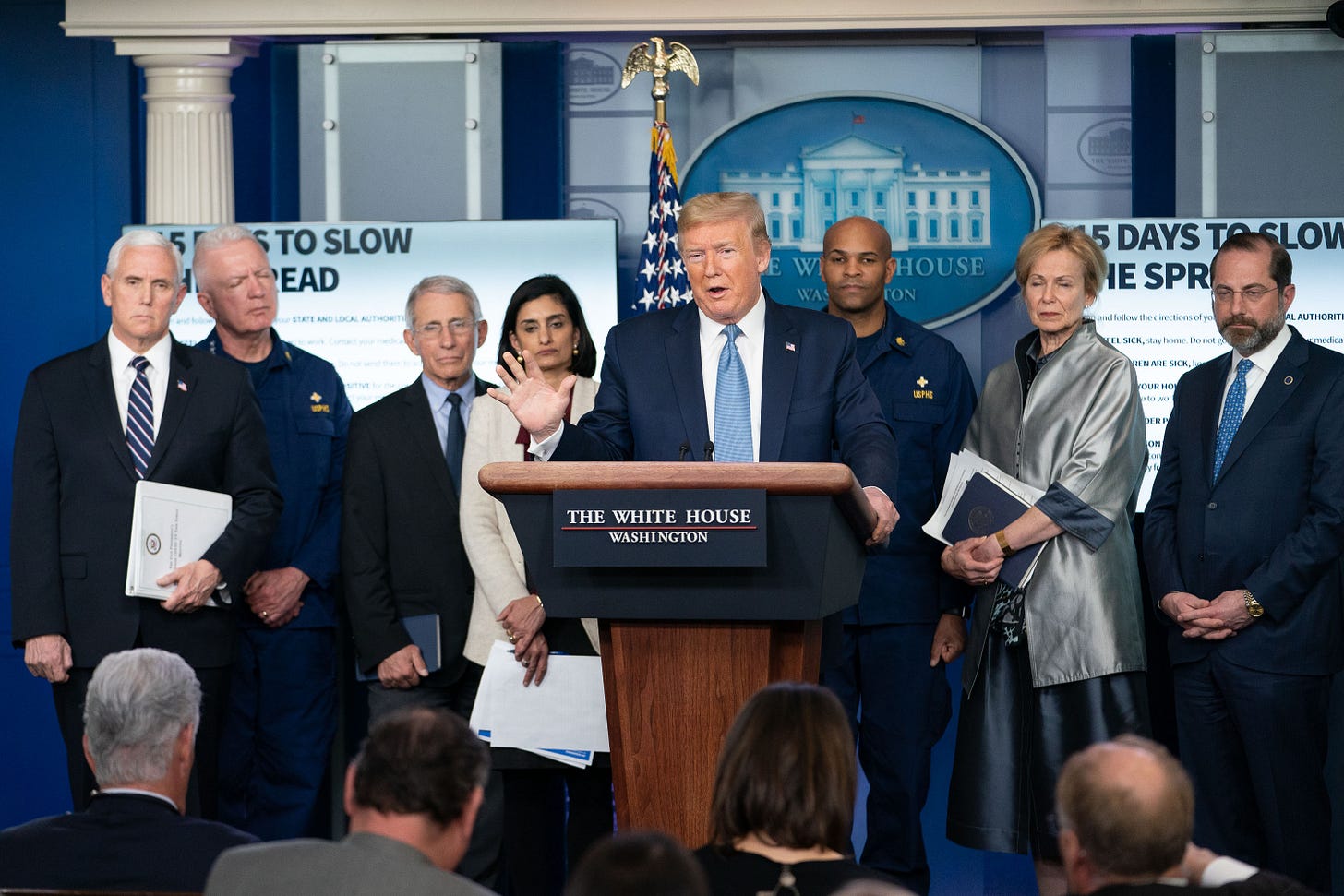

The bad old days.

Perhaps the greatest mystery of this election season is why Democrats continue to get blamed for an inflation spike that peaked more than two years ago, while Republicans avoid blame for the 100,000 to 400,000 excess Covid deaths in the United States under Trump that public health experts attribute to government mismanagement. Under Biden, people paid more for laundry detergent. Under Trump, a cohort roughly equivalent in number to the population of Ann Arbor, Michigan, at the low end, and Cleveland, Ohio, at the high end, died merely because they had the bad luck to inhabit the United States.

We can argue about precisely how much these excess deaths were Donald Trump’s fault, but Trump’s denial of the crisis and his refusal to allow the federal government to take a leading role in fighting it unquestionably contributed significantly to the body count. By contrast, the inflation spike was at best marginally affected by government spending to address the crisis (which, people seem to forget, included two large appropriations under Trump). Government policy concerning inflation resides almost exclusively with the Federal Reserve, whose chair was initially appointed by Donald Trump. Yet Trump has managed to persuade everyone that his final year in office—the Covid year—shouldn’t count, even as he blames Biden for an inflation spike caused mostly by the pandemic he mismanaged.

It’s no surprise that Trump downplays Covid, but it is surprising that the press and even to some extent the Harris campaign go along with it. At least part of this reflects an historic tendency to want to forget public-health catastrophes as soon as they’re over. My 831-page high school American history textbook, published in 1973, made no mention of the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, even though it killed more people than World War One. “For many,” Elizabeth Outka explains in her excellent (and remarkably well-timed) 2020 book Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature, “there was something humiliating about dying of the flu in wartime.” But other factors suppressed memory, too, including the pandemic’s “random unfairness,” which defied efforts to identify “enemies, scapegoats, and heroes” and required recognition of what the pandemic’s best-known historian, John Barry, called “nonhuman violence.” Virginia Woolf, in her essay “On Being Ill” observed that “the public would say that a novel devoted to influenza lacked plot.” (Woolf herself contracted Spanish flu several times and lost her mother to it, and defied the trend by incorporating influenza into the plot of Mrs. Dalloway.)

Trump, of course, tried to scapegoat China for being the source of the virus, but Trump’s own avoidance made him the true villain in the United States, worsening Covid’s nonhuman violence relative to that in other comparable nations. A central argument against re-electing Trump, it seems to me, is his demonstration during that last year in office that he was thoroughly unable to manage any kind of crisis—a pandemic, a war, a crippling cyberattack, a severe economic downturn, you name it. That is the subject of my latest New Republic piece. You can read it here.

Maybe the Dems can't address Trump's role without acknowledging their own unwillingness to be serious about the pandemic (and about the risk of future pandemics) for four years under Biden.

Because there's been a rear-guard movement on the right downplay how bad it was. Far too many people believe the response to it was more harmful than letting bodies pile up as Trump allowed.

It may not even be a net positive to raise the issue.