We Pay A High Price for High Voter Participation

It's great that more people vote in presidential elections than at any time since 1900. But the sad truth is that people don't run to the polls in record numbers when times are good.

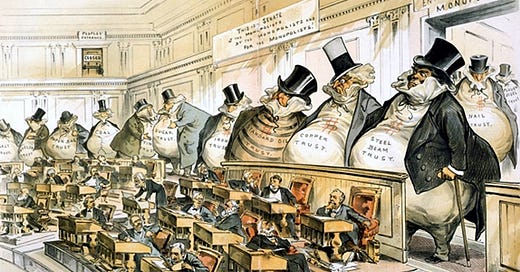

The golden age of voter participation. “Bosses of the Senate,” by Joseph Keppler, published by The Puck in January 1889.

If you’re reading this, odds are that you will vote in the November election. More people voted in 2020 (66 percent of all eligible voters) than in any election since 1900. That data point is more impressive when you remember that in 1900 the pool of all eligible voters, as a share of the overall population, was less than half what it is today because women were ineligible to vote; African Americans were shut out throughout the South; and the minimum voting age was 21. The proportion of eligible voters who participate in 2024 could well exceed 66 percent.

I remember a time when good-government liberals like the late Curtis Gans, co-founder of the now-defunct nonprofit Center for the Study of the American Electorate, would have celebrated voter participation this high. In many ways it is something to be grateful for But the unhappy truth is that high voter participation rates are associated not with good times, but with bad. When this many people dash to the polls, it’s because, as the late Tony Judt would say, the land fares ill. In the United States, voting participation reached its all-time high between 1840 and 1900, which were the most divisive and, later, corrupt years in American history. They included a runup to civil war; the Civil War itself; and the grimly chaotic period that followed, encompassing (if we include 1901) three presidential assassinations, the Northern retreat from Reconstruction, and the Gilded Age.

I’m delighted voter participation is setting records, but I wish it weren’t because the Republican Party has turned proto-fascist. The only good news is that the GOP’s orange Duce, Donald Trump, is more popular with people who don’t vote than with people who do. But he’s working on getting these stragglers to the polls, and I think Democrats should be matching his efforts, because Mr. Infrequent Voter (he’s usually a guy) isn’t as conservative as he thinks he is. That’s the subject of my latest New Republic piece. You can read it here.