These are the times that try men's souls

Tom Paine's New Rochelle.

I used to fish here, and skate in the wintertime. The fishing wasn’t great; all you could catch were carp, which I threw back. The skating was better but I never was very good at it (and I’m worse now). The pond was too dirty to swim in when I lived here half a century ago, and it appears to remain so. This photograph was taken (by my wife, Sarah) earlier this week near the end of a very hot day, and nobody was in the water.

It’s a lovely spot, and in 1968 Larry Peerce used it as the backdrop for a scene in his middling adaptation of Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus, with New Rochelle standing in for Short Hills, New Jersey. Short Hills is the hometown of Brenda Patimkin (Ali McGraw), the Radcliffe goddess whose failure to hide her diaphragm precipitates a family crisis that must puzzle youngsters who stream the film today. (The book is still great, though.) I was 10 at the time, and not conversant in methods of contraception, or even what “contraception” meant, and if asked to identify what a diaphragm was, I would have said (if anything) that it was the muscle we all use to breathe. I was away at summer camp during the few days Hollywood descended on my neighborhood, and missed all the excitement, and when Goodbye, Columbus arrived in theaters the following spring my parents judged me too young to see it. The following year we moved to Southern California, and Hollywood lost much of its novelty.

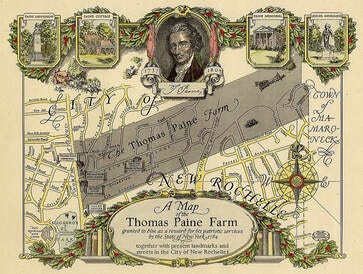

I call it a pond, which obviously it is, but the locals named it after the great lower-case-r republican Tom Paine and called it a lake. Paine Lake stands across Paine Avenue from Thomas Paine Cottage, which a grateful New York State in 1784 bequeathed to Paine along with 300 acres of farmland, seized after the American Revolution from a Tory Loyalist named Patrick DeVaux. The house I grew up in to the age of 12 (which Sarah and I also visited) was built on land that once lay at the western end of Paine’s farm. Much of the area also lay inside the containment zone that Gov. Andrew Cuomo created in early March, when New Rochelle could boast the largest Covid-19 cluster in the U.S. They could have called it the Thomas Paine Zone.

Paine was living in New Jersey when he was given the farm, and then travelled back to London, where he wrote The Rights of Man, an attack on monarchism that got him chased out of England. An admirer of the French Revolution, Paine went to Paris and joined the revolutionary government, but eventually he fell afoul of Robespierre, was thrown into jail, and narrowly escaped the guillotine. The American ambassador to France, James Monroe, got him released, and Paine, now an old man, returned to America, finally taking possession of his New Rochelle farm. He lived there four years, from 1802 to 1806, and was buried there after he died in Greenwich Village in 1809.

Paine’s most-quoted words appeared in The American Crisis, a series of pamphlets published in 1776 and 1777. The first of these pamphlets begins:

These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph…. Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.

For some readers, this passage may bring to mind the current president of the United States (who after his 2016 election was described by Roth as “destitute of all decency”). Trump is working openly to withhold funding for mail-in balloting, which, he complains, favors the opposite party. Although he himself intends to vote by mail, just as he did in the primaries, Trump insists, in the absence of any evidence, that mail-in ballots are susceptible to fraud. Trump is doing this in the midst of the Covid pandemic, which has become, by one recent estimate, nearly as deadly as the 1918 outbreak of Spanish flu (which killed about 675,000 people in the United States), largely as a result of Trump’s own chaotic leadership. Covid-19 could make a trip to the polls on Nov. 3 a mortal threat, especially to the older voters who until recently were among Trump’s most fervent supporters. Nonetheless, Trump opposes voting by mail, even as he prepares to cast his own vote by mail.

Trump has also been praising, as a “future Republican Star,” Marjorie Taylor Greene, who won a Republican primary earlier this week in Georgia in spite of her vocal support for QAnon, a hateful far-right group that inveighs against (in Greene’s words) a “Global Cabal of Satan worshiping pedophiles” led by Hilary Clinton and George Soros. (Which doesn’t, I feel obliged to add, exist.) The FBI has identified QAnon as a potential source of domestic terrorism. Asked about Greene’s QAnon connection today, Trump would say only, “She won by a lot” and “She comes from a great state.”

Trump has also questioned whether Kamala Harris, Joe Biden’s pick to run for vice president, is eligible to do so, returning to the fraudulent and racist birtherism that launched his political career.

This has all happened just in the past few days.

But we were talking about Tom Paine. Paine was, as I say, buried in New Rochelle. But he didn’t stay there. In 1819 his body was disinterred and stolen by the English pamphleteer William Cobbett. Cobbett, a Loyalist during the Revolution who’d attacked Paine repeatedly, later decided (based partly on his horror at the Peterloo massacre) that Paine had been right about British monarchy after all. Observing that America no longer revered Paine (who late in life picked an ill-advised fight with George Washington), Cobbett decided that the man ought to be buried in England. So in the dead of night Cobbett dug Paine up, believing “those bones will effect the reformation of England in Church and State.”

When Cobbett returned to England in triumph with Paine’s remains and a grand plan to house them in a mausoleum, he was greeted with derision. “The English hate melodrama,” the Liberal Party MP Charles Milnes Gaitskill would later explain, “and had plenty to do besides admire Tom Paine’s remains.” Lord Byron captured the mood in this epigram:

In digging up your bones, Tom Paine,

Will Cobbett has done well:

You visit him on Earth again,

He'll visit you in Hell.

The mausoleum was never built, and the bones in question, situated for a time in a Liverpool customs house, passed on after Cobett’s death to a day laborer, then to Cobbett’s secretary, and then to a furniture dealer. After that, the trail goes cold; nobody knows where Paine’s bones reside today. But Paine’s brain stem is reputed to have remained in New Rochelle, and to be buried in mummified state someplace on or near the site of Paine’s farm, just a few paces from where Neil Klugman takes a stroll with Brenda Patimkin after playing a game of tennis in Goodbye, Columbus.

Update: Eric Alterman, who grew up one town over in Scarsdale, informs me that the film of Goodbye, Columbus, which probably doesn’t deserve all the attention we’re giving it here, shifted Brenda’s hometown from Essex County, New Jersey, to Westchester County, New York, possibly because Paramount chief Frank Yablans lived in Scarsdale, and that filming scenes for the movie in New Rochelle, Scarsdale, and White Plains therefore made, at least arguably, some narrative sense. I think Eric would agree that moving a Roth character out of New Jersey is at least as brazen a desecration as moving Tom Paine’s bones out of New Rochelle, though it doesn’t seem to have attracted as much comment at the time. When the movie came out Roth was known to the public as the bad-boy author of the just-published, wildly popular Portnoy’s Complaint, and not the revered, Library-of America-certified litterateur of his final years.

Love how this piece comes together!