The Best War Correspondent I Ever Saw

Covering a war is "like putting a finger in a live electric socket while trying to take notes with the other hand."

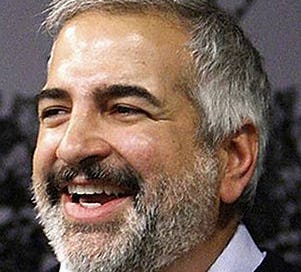

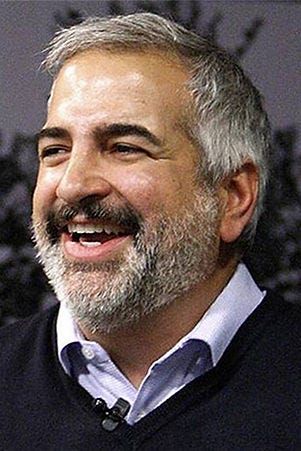

Anthony Shadid (1968-2012), war correspondent for the Washington Post and New York Times.

The success of the film Civil War has me thinking about a fundamental contradiction of war reporting: The horrors of conflict push people toward becoming desensitized as a matter of self-protection, yet to do the job well, one must maintain an emotional openness.

A big part of the job is figuring out where you should be, and then getting yourself there. Related to this is keeping yourself alive. But you can’t protect yourself by taking refuge in insensitivity, for two major reasons.

The first is tactical: One of the keys to survival is being extremely alive to what is going on around you—or not going on. I remember being in an obscure neighborhood in Kabul, Afghanistan, not long after the American invasion. I was reporting for the Washington Post. The Afghan I was with realized at the same moment I did that no people were around, nor even sheep or goats. Indeed, the grass around us was tall and thick, unusual in a desert city where animals tend to be ravenous.

The training I had received from the U.S. Army years earlier in dealing with land mines kicked in. (Thank you, Army.) If you find yourself in a place where animals should be grazing and people should be, but aren’t, you may be in a minefield. My colleague and I backed up the way we had come in, using the same footsteps. A few minutes later we were back on Darulaman Road, where traffic was heavy and sheep chewed on scraps.

The essential warning signs may not always be that obvious. A Post colleague of mine back then, Marc Kaufman, was in a car west of Kandahar, Afghanistan, that went around a curve. At that point, Marc’s “spidey sense” kicked in. Something seemed off. He couldn’t discern quite what it was, but just that a threat seemed to be nearby. Maybe it was nerves, or maybe his unconscious had picked up something that he hadn’t yet articulated. But there was no reason to push things. He turned around.

The other reason to maintain acute sensitivity is that you need it to do the job well. You want all your senses to be working in overdrive to really grasp what is happening in a war around you at a given place at a certain time. Not just what people are saying and what they are doing, but their expressions and tone of voice. Sometimes there is an important discrepancy between what a person says and how his or her face looks as it is said. Often, in Iraq, I found a huge difference between what American officials were saying in the Green Zone and how things felt out on the streets of Baghdad. To report well, you have to keep that all in mind.

The best war correspondent I ever saw in the field was Anthony Shadid, who twice won the Pulitzer Prize for foreign reporting. He also won two George Polk awards. I worked with Shadid in Iraq when we were both on the staff of the Post. He later reported for the New York Times in Libya and Syria. Anthony was an emotional, sensitive man. One example: In May 2003, I walked along with a U.S. Army patrol in western Baghdad, recording their comments and interactions with Iraqis. He, with the knowledge of the soldiers I was with, trailed us, speaking in Arabic with the locals. At the end of the patrol, Anthony was almost apologetic as he sat down with the soldiers and told them that the old people and children didn’t much mind the American presence, but that the young men loathed them. This was a genuine surprise to the soldiers. Anthony read quotations to them from his notes.

Anthony remained studious, insightful and humble. One night in Baghdad about a year later, as we listened to machine gun fire and mortar shells landing about two miles south of us, he remarked that, “The more I know about Iraq, the less I understand it.” I think the best reporters strive to maintain such humility and openness.

But remaining sensitive in a war zone isn’t easy. I liken it to putting a finger in a live electric socket while trying to take notes with the other hand. After a few minutes, your socketed finger may be blackened, your heart racing, and your face dripping in sweat—but you are doing your job. Now go out and do that every day.

Living like that carries costs. Some war reporters in Iraq wound up getting out of the business altogether. Others wallowed in alcohol, or became hermetic. I wrote about my own difficulties here. I recently had lunch with a veteran war reporter who did several tours in Iraq. He commented, “I feel angry all the time.”

As for Anthony Shadid, the best of them, he died in 2012 on the Syrian-Turkish border while reporting on the war in that area, twelve days before publication of his memoir House of Stone. He was only 43 years old. Some said he was killed by an extreme asthma attack, others that he suffered a heart attack. I suspect he had simply seen and done too much, and that his system gave out.

A beautiful tribute. I feel fortunate to have had the chance to read his reporting -- and yours.