Popularism v. Deliverism

Count me out on both. Why we shouldn't elevate political strategy to ideology.

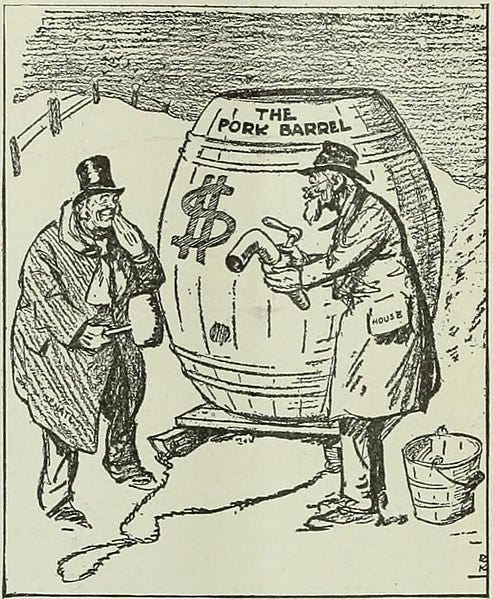

New York World, 1917

I’ve observed from a safe distance the war between popularism, a word coined (or at least popularized) by the Democratic political consultant Sean McElwee, and deliverism, a word coined by the antitrust policy wonk Matt Stoller. There’s much to be said for both sides of this argument, which is as old as representative democracy itself. Should politicians follow their constituencies (popularism) or lead them (deliverism)? Um, yes. Pouring old wine into new bottles, popularism vs. deliverism leaves the conflict no more resolvable than it ever was.

But I object to the bottles. The new framing, it seems to me, hardens tactical questions into “isms,” which is to say, ideologies. That blurs a necessary and important distinction between political means and political ends at a moment when the Republican mainstream has already ceased to recognize any difference. I don’t want to follow them down that rabbit hole.

Like “populism” before it, “popularism” is a mostly pejorative term, applied more often by its enemies than its friends. Although McElwee uses the term, as best I can tell the Democratic numbers-cruncher David Shor, its leading proponent, does not. Nor does White House chief of staff Jeff Zients, popularist-in-chief inside the Biden White House.

The closest thing to a popularist manifesto is a sympathetic interview with Shor that Ezra Klein published in The New York Times in October 2021 (“David Shor Is Telling Democrats What They Don’t Want To Hear”). Klein related how Shor had lost his job for tweeting, during nationwide protests over the police killing of George Floyd, some research suggesting that civil rights protests help Democrats when they remain nonviolent and hurt them when they don’t. It was a bona fide cancellation by the left, but, as Klein noted, it “turned him into a star.”

To Shor, popularism is mostly about moving Democratic Party policymaking back toward the center. There are exceptions, Shor said, including prescription drug price negotiation for Medicare (which finally became law in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, and is now being implemented amid howls of protest by Big Pharma). Drug price negotiation might be a liberal policy, Shor told Klein, but it was wildly popular; one month earlier he’d tweeted that prescription drug polled better than any other of the 194 policy proposals he’d tested that year.

In general, though, Shor argued that popularist policies required Democratic party professionals to shift rightward. “If you look inside the Democratic Party,” Shor told Klein,

there are three times more moderate or conservative nonwhite people than very liberal white people, but very liberal white people are infinitely more represented. That’s morally bad, but it also means eventually they’ll leave.

“Most voters don’t like dramatic change,” McElwee told me. Who are the most popular politicians? he asked. Republican governors in Democratic states. “They don’t do any big policy changes in any direction.” Who are the most unpopular? Governors and presidents who enjoy bicameral legislative majorities, because they overreach. He cited the examples of President Barack Obama passing the Affordable Care Act and President Donald Trump trying to repeal it. Two moves in opposite directions; both unpopular.

There’s a lot of truth to this. But it’s worth remembering that Shor’s application of this theory to the midterm elections, which were one year in the future when he talked to Klein, turned out to be quite wrong. Shor predicted that Democrats would lose big in both the Senate and the House. Neither happened, and the Democrats—barely—kept their Senate majority. A big reason was that eight months after the interview, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade—an issue of vast importance to left-leaning party elites, but also to the broader Democratic electorate.

One problem with popularism as an ideology (rather than a practical check on ideology, as it used to be) is that it isn’t always easy to know what’s popular and what isn’t. A 2013 study by David Broockman and Christopher Skovron, then graduate students in political science at Berkeley and the University of Michigan, found that liberal and conservative state legislative candidates both overestimated how conservative their prospective constituencies were. Conservatives overestimated the conservatism of the electorate by 20 percentage points, but liberals overestimated it by more than 10. “Perversely,” they wrote, “liberal politicians were broadly congruent with their constituents but in many cases unaware of this congruence.” Like star-crossed lovers, politicians and voters who were made for one another were separated by misconceptions.

Popularism offends the left, of course. The left answered with an ideology of its own: deliverism, a doctrine that echoes Kevin Costner’s injunction, in the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, to build a baseball diamond in his Iowa cornfield (“If you build it, they will come”). But you really have to build that baseball diamond. Every time Democrats make a promise and fail to deliver, David Dayan wrote in The American Prospect four days after Klein published his Shor interview,

cynicism finds a breeding ground. People tune out the Democratic message as pretty words in a speech. Eventually, Democratic support gets ground down to a nub, surfacing only in major metropolitan areas that have a cultural affinity for liberalism.

That’s true, but Dayan’s example—Medicare drug-price negotiation—was faulty. Dayan argued that Biden should achieve this administratively, or at least threaten to do so. Instead, the following year Biden won legislative authority to negotiate Medicare drug prices, which was better. Often it takes a few years for Democrats to get something done. That’s an argument for planting the flag and then scouting your opportunity, not against it.

In June the journal Democracy published an article by Deepak Bhargava and Shahrzad Shams, both of the nonprofit Roosevelt Institute, and Harry Hanbury, a documentary filmmaker, that made a common-sense argument against deliverism (“The Death of ‘Deliverism’”). “In exchange for enacting [progressive] policies,” they wrote, “deliverism holds, voters will reward progressives at the ballot box.” But

progressive economic policies do not necessarily lead to the political outcomes that deliverism predicts they should, and deliverism is proving ineffectual as a response to authoritarianism…. The emotional alchemy of the authoritarian approach is so strong that it can override facts and material reality.

Actually, I’d argue that even less fearsome standard-issue Republicans often sucker-punch Democrats through “emotional alchemy.” The 2010 midterm verdict on Obamacare, which returned the House to the Republicans, along with 29 governorships and a stunning 690 seats in state legislatures, was thumbs-down. Never mind that most voters stood to gain from the Affordable Care Act and, as McElwee notes, were just as furious when Trump tried to take it away.

What’s the solution? The Democracy authors recommend a variety of psychological strategies that strike me as a little woo-woo, including something about rhesus monkeys seeking maternal comfort that I can’t follow. (I should concede here that this is not a subject on which I claim expertise). I suggest a simpler solution: Stop thinking of campaign strategies as ideologies.

The popularism-deliverism impasse is an ideological fight disguised as a strategic one. The popularists lean right within the Democratic Party spectrum, and the deliverists lean left. Of course they want to do different things. But you can’t apply a cookie-cutter ism to win elections in all 50 states, much less 435 congressional districts and I-don’t-know-how-many state legislative districts. Insisting there’s One True Path to victory is a recipe for defeat.

This impasse also ignores a third approach to governance that constitutes at least part of every policy decision that a president or senator or representative makes, and sometimes more than part. Unlike the two others, this one really is rooted in ideology. Let’s call it, for want of a better term, Do-It-Because-It’s-Right-Even-Though-Voters-May-Not-Thank-You-For-It-ism. It’s an approach that doesn’t reduce every problem to a polling question or a power grab. Sometimes a politician must follow this imperative even when he knows, as Lyndon Johnson purportedly did when he signed the Civil Rights Act, that your party is going to lose a large constituency (in that case, Southern whites) as a result. Sometimes—often, I’d argue—the demands of sound policymaking dictate what a politician does to the exclusion of everything else. You can cross your fingers and hope the public will reward you, but you’ll never actually know, so you might as well do what you believe right.

Even Republicans used to do this from time to time. Now there isn’t much room for it because GOP politics has become wholly performative: ban books, promote child labor, say January 6 was no big deal, bully the House Speaker to show you can. It’s not exactly popularist, because most Republican voters (I hope) don’t believe this crap, and it's certainly not deliverist, because the last thing Republicans—congressional ones, anyway— want to do is deliver the extremist outcomes they purport to favor. Look what happened when their majority-reactionary Supreme Court took away women’s right to abortion.

GOP behavior is an unwholesome elevation of political strategy to ideology. I’ve written that there’s no such thing as GOP ideology anymore, but I ought to have conceded one: an ideology that says you must be willing to say and do anything to win re-election, and you’re never not running for re-election. I’ve argued here that neither popularism nor deliverism will reliably deliver electoral victories, because a rigid commitment to one or the other, as opposed to blending both approaches according to circumstance, is bad strategy. But if one or the other turned out to be good strategy I’d still be wary, because political strategy should serve ideology, and not the other way around. It’s trite to say we need Democratic politicians guided by principle and a strong commitment to helping people. But it’s true. No ism should ever displace that.