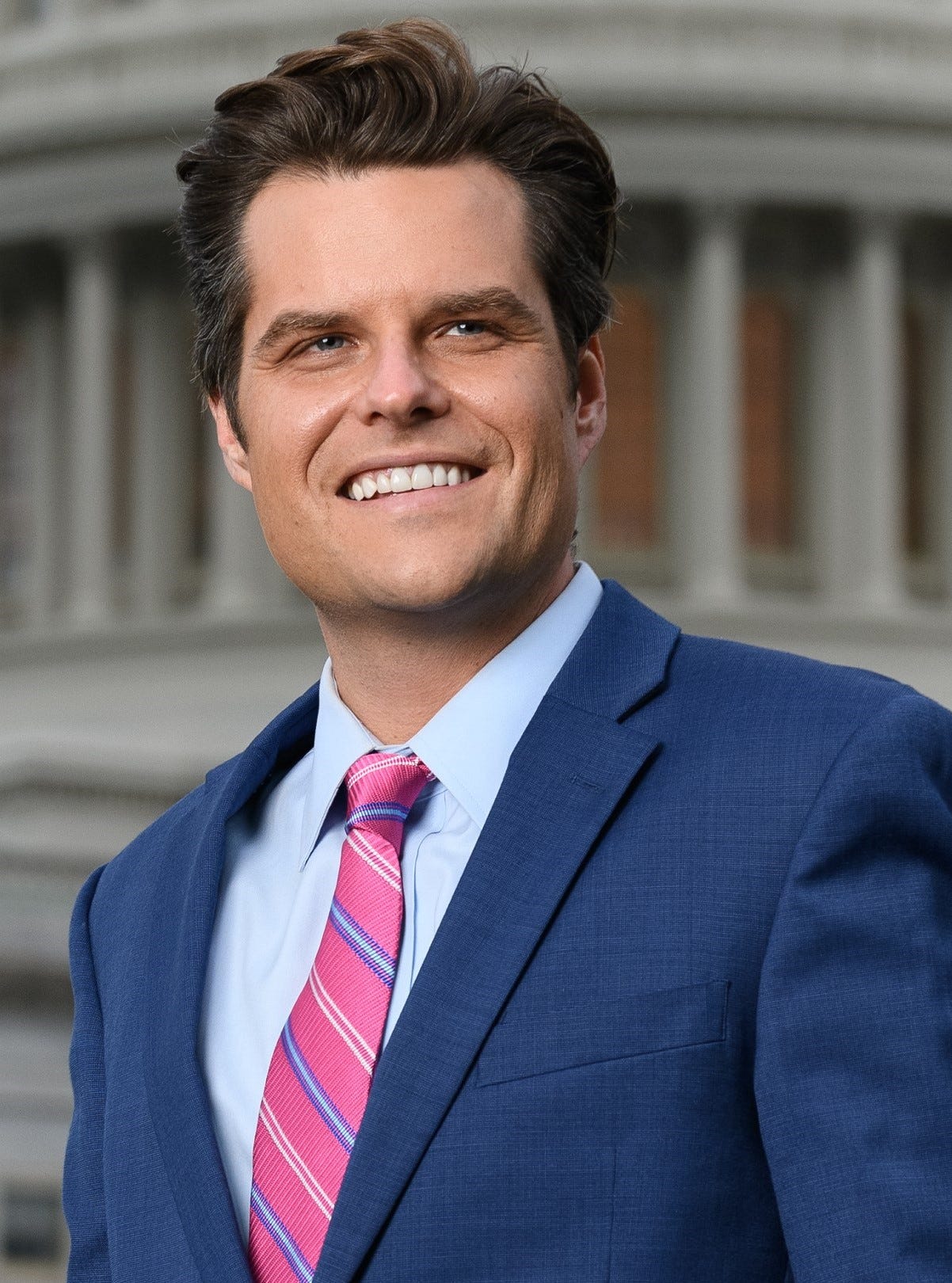

Matt Gaetz, hypocrite

The poverty pimp's son who hates welfare dependency.

Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida held up House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s debt-ceiling bill with the demand that the bill’s expansion of food-stamp work requirements to “couch potatoes” (Gate’s term) aged 49-55 be imposed in 2014 rather than 2015. Shortly before Wednesday’s vote, in which McCarthy’s bill squeaked by, 217-215, the bill was hastily rewritten to accommodate Gaetz; starting in October 2024 quinquagenarian food-stamp recipients will have three months to get a damn job or lose their benefits. Gaetz voted against the bill anyway because (he boasted) he has never in his life voted to raise the debt ceiling. That doesn’t speak well of McCarthy’s horse-trading prowess.

Is there anything more grotesque than a declared enemy of the welfare state—Gaetz calls himself a “libertarian populist”—who’s grown wealthy off it? Here’s how Stephanie Mencimer explained it in a 2019 Mother Jones profile:

In the late 1970s, his father co-founded a nonprofit hospice company that successfully lobbied Congress to allowMedicare and Medicaid to cover its services. Once the public money started flowing, the nonprofit became a for-profit corporation, Vitas, that grew into the country’s largest hospice care provider.

In 2004, Don Gaetz and his partners cashed in, selling the hospice company to the parent company of the plumbing behemoth Roto-Rooter for $400 million. When he ran for state Senate two years later, Don had a net worth of $25 million. In 2013, the Justice Department sued Vitas, alleging that between 2002 and 2013, the company had defrauded Medicare by filing false claims for services never provided or for patients who weren’t terminally ill. The company settled the case in 2017 for more than $75 million, at the time the largest settlement ever recovered from a hospice company. (Don wasn’t named in the case and has denied any wrongdoing.)

Well, that’s Don, you say, not Matt. (As Al Pacino tells Diane Keaton at the start of The Godfather, “That’s my family, Kay, it’s not me.”) But it was Don’s poverty-pimping (I’ve written about this variety before) that made possible Gaetz’s entry into politics. Gaetz was able to spend $100,000 in personal funds on his 2010 primary campaign for the Florida state legislature, Mencimer reported, “more than any other candidate’s total fundraising haul,” even though he earned only $29,000 from his law practice that year. Six years later, Gaetz gave $200,000 to his first congressional campaign, an amount that once again exceeded any of his primary opponents’ total haul, even though $200,000 represented more than half Gaetz’s recorded net worth. In both instances the expenditures were made possible, it appears, by cash transfers from Don, in the latter case through real estate transactions involving a company, Treveron, that Don owned, and on which Matt was listed as a vice president. Astonishingly, that arrangement was probably legal, if barely so.

What were we talking about? Oh, welfare dependency. For four decades Republicans have been tacking work requirements onto the food-stamp program as their price for letting it live. By now we should have some pretty good evidence that work requirements move unemployed food-stamp recipients into work, right? Except we don’t. Pick a study, any study. This one’s from February 2023, and was published in the American Economic Journal. From the abstract:

We find robust evidence that work requirements increase program exits by 23 percentage points (64 percent) among incumbent participants. Overall program participation among adults who are subject to work requirements is reduced by 53 percent. Homeless adults are disproportionately screened out. We find no effects on employment….

Work requirements aren’t a way to end welfare dependency. They’re a way to deprive poor people of food stamps. That’s the subject of my latest New Republic piece. You can read it here.