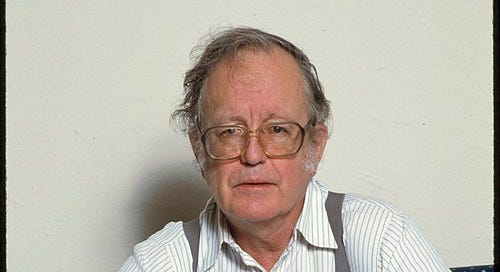

Wilfrid Sheed in August 1987, photographed by Bernard Gotfryd.

Near the end of his life I entered into an email correspondence with the novelist and critic Wilfrid Sheed. He sent a letter to Slate, where I then worked, expressing what I now recognize to be sound criticism of something I’d written. I replied “Never mind that, I’m an enormous fan of yours, your books occupy a whole shelf in my bookcase,” or words to that effect. We had a lot of friendly back and forth after that, but alas I failed to save our exchanges when Slate’s email switched over from Microsoft to the Washington Post Company in January 2005 (a highly distracted month for me; on the 16th my first wife died from liver cancer). Thus the only evidence of our epistolary friendship is that he ended up writing a handful of pieces for Slate, and I wrote a remembrance when he died in 2011. Once, while visiting friends in Sag Harbor, where Sheed lived, I arranged to meet him for lunch, but he wasn’t well on the appointed day and so we didn’t.

I mention Sheed because I often think of him on Father’s Day. He wrote what is perhaps the best-ever essay on American fathers, and what he made of them as a preteen wartime refugee from England, and how his father failed to measure up, and how he came to realize that was because he surpassed most of them. The essay is titled, simply, “Fathers,” and it concludes his 1990 collection, Essays in Disguise. Sheed published multiple essay collections, and you should read them all. The novels are less perfect than his essays, but Max Jamison and People Will Always Be Kind are largely unrecognized classics. (Hey New York Review Books, get on the case.)

Anyway, here is a snippet from Sheed’s “Fathers”:

The approach of Visitors Day [at boarding school] brought my embarrassment to a veritable Woody Allen crescendo. Why, my mother couldn’t even cook, for Pete’s sake (although perhaps that’s a story for Mother’s Day), and they both spoke in rich English accents, which my comrades had drilled me to believe was the fruitiest sound in God’s creation. My father would probably say ‘pip pip’ or something and we would just have to run for it. By then the other fathers would have marched in like a Marine platoon, lean and leathery and covered in engine grease, while my father looked for his glasses.

I was actually considering pretending not to know my parents at all, when the other guys’ sires began parading around the ring. I stared at them in disbelief. This couldn’t be right. For instance, that pipsqueak over there couldn’t be Buth Petrillo’s dad, could he? Or Slugger Hogan’s or Mad Dog Maguire’s either. They must have been substitutes. These fellows looked like bank clerks.

All right, one or two of them looked okay, but some fathers were in even worse shape than mine, and almost all looked older and tireder and manifestly less at ease. Frank’s eyes lit with recognition. “Ah, there you are, Wilfred.” Nobody laughed. The egghead sailed through the fishermen like a flagship.

He then proceeded to do the unthinkable: he started a conversation with a son or two other than his own. He also talked to their parents, who seemed sincerely grateful; he even made one of them laugh, a brief startled cackle….

My father’s technique was much harder than it looked, like most works of art. But there were two aspects to it that are within reach of any duffer. If a kid was rude to him, he was usually rude right back. (“I wouldn’t take that from a grownup; why should I take it from you?”) And he never escaped into heartiness: “Hi, Bill! My son Biff has told me a lot about you,” etc. Such indiscriminate babble is almost worse than not talking at all. No fellow human, however small, should be subjected to “How do you like your school, sonny?”

We lost a master when Sheed died 14 years ago. Happy Father’s Day, Bill.