Happy birthday, Charlie Peters

He taught us that government is not the problem. Indifference to how well or poorly government carries out its duties is what makes us believe that it is.

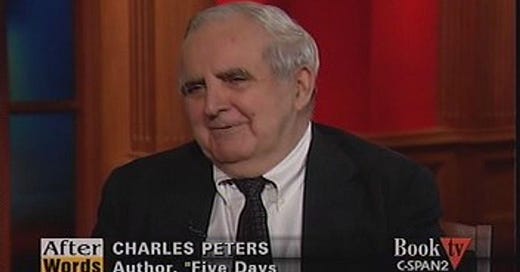

Today is the 95th birthday of my mentor, Charles Peters. Charlie founded the Washington Monthly in 1969 after serving as director of evaluation at Sargent Shriver’s Peace Corps. He was editor-in-chief of the Monthly until 2001. The Monthly’s Matthew Cooper has posted a lovely tribute to Charlie here. Links to some of Charlie’s books can be found here. (My favorite of these is Five Days in Philadelphia, his account of the 1940 Republican convention, which in effect made possible the U.S. entry into World War Two. But you also can’t go wrong with We Do Our Part, a summing up of Charlie’s ideas about how to restore the spirit of the New Deal.)

Charlie created the Monthly to expand work he’d been doing at the Peace Corps. The department of evaluation, which he created in 1962, sent Washington-based staff out into the field to assess whether Peace Corps programs were achieving what they were supposed to achieve. Charlie found that civil servants weren’t great at this task, because they were trained to perform narrow green-eyeshade audits that looked for improprieties, not wide-angled evaluations that assessed whether the foreign populations served by the Peace Corps were getting much of anything useful out of the arrangement. So Charlie hired established journalists instead, like Calvin Trillin and Russell Baker and Murray Kempton. (Charlie had a preference for witty journalists; in hiring, he always tried to steer clear of anybody who displayed no sense of humor.) People would be scandalized today to learn that journalists freelanced for a federal agency, but in those days nobody much cared, and it’s not like the Peace Corps was the CIA. Eventually Charlie decided every federal agency could benefit from this type of evaluation, and to carry these out he started the Monthly.

The Monthly has evolved over the years, but under Charlie’s successor, Paul Glastris, it’s still largely committed to examining whether domestic policies achieve their stated goals and whether the public benefits as a result. The purpose of this exercise is not to prop up a pro-government or anti-government ideology, but rather to consider how government policies might be carried out more effectively, to the greater benefit of all. The underlying assumption is that government can be a force for good, and that Ronald Reagan was wrong in 1981 when he said government can’t solve our problems because government is the problem. Government can solve our problems, but there’s no guarantee it will, so citizens need to pay pragmatic attention to how well or poorly it’s doing its job. When they don’t, their cynicism is liable to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The point seems an obvious one, but journalists today remain resistant to doing this kind of reporting unless some sort of scandal puts a government agency on Page One. The question of whether democratic governance is effective is judged too dull to devote resources to. After he left the Monthly, Charlie ran a foundation, Understanding Government, that offered funding to anybody who wanted to pursue this question, but he ended up giving nearly all his grants to academics, because most reporters didn’t really give a damn.

A favorite theme of Charlie’s is that one person can make a much bigger difference in the lives of others than he or she is likely to realize. Charlie made a big difference in my life. I chucked a very good job as an editor on the New York Times op-ed page in 1983 to go work for the Monthly at one-third the pay. My parents, who worshipped the Times, were perplexed. Max Frankel, who was my boss, was more than perplexed; he was annoyed. Later, when I tried once or twice to return to the Times, I found my path blocked. But joining the Monthly was still the right choice. Editing and writing for Charlie was an education that was unavailable anywhere else, and after I performed the standard two-year tour (a tradition established earlier by Taylor Branch, who took Charlie out to lunch and explained very gently that much as we all loved him, nobody could endure his eccentricities much longer than that) I acquired a warm lifelong friendship with Charlie and his wife, Beth Peters.

So happy 95th, Charlie, and many happy returns.

![The Washington Monthly] 25th Anniversary | C-SPAN.org The Washington Monthly] 25th Anniversary | C-SPAN.org](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F60dd2812-33ff-4360-98b0-09e66fa6add7_1024x576.jpeg)

Very nice tribute.

Lovely piece, Tim!