Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the First Thanksgiving

Exactly one fact that they taught me in third grade turns out to be true.

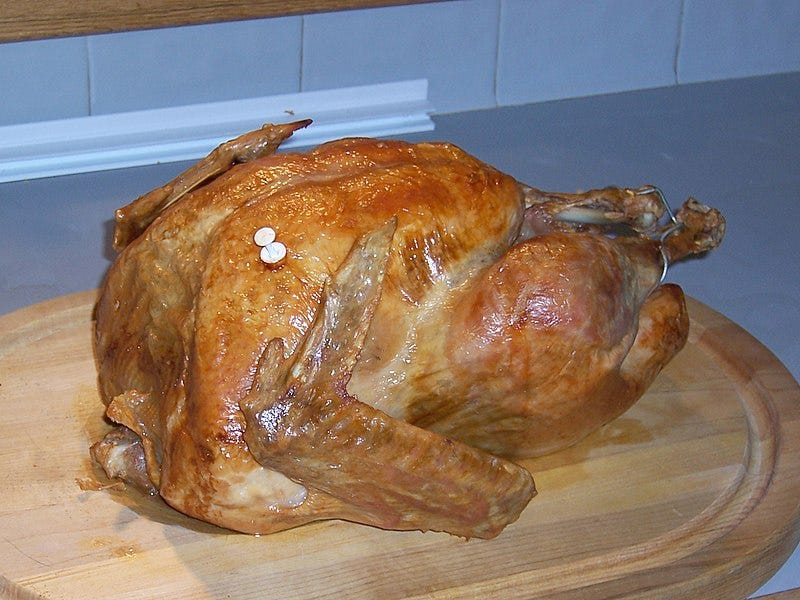

Did they serve turkey at the first Thanksgiving? Probably not, but if they did it definitely didn’t have that little plastic pop-up thingy to tell you it was done.

Happy Thanksgiving! Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday because it’s relatively relaxed, because it’s an occasion to appreciate what we have (politics aside), because it’s mostly about food and family, and because it celebrates a brief multicultural moment in American history, albeit one that didn’t happen the way you were told. I’ve learned this from various online sources and from the late Godfrey Hodgson’s 2006 book A Great and Godly Adventure: The Pilgrims and the Myth of the First Thanksgiving, which I finally pulled down from my shelf a few days ago.

And now I’ll be happy to take your questions.

The Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, right?

No. They landed first, in 1620, in Cape Cod, where the very first thing they did was steal some corn stashed for safekeeping by Native Americans. They decided the Cape was unsuitable and proceeded to Plymouth, where the soil was better (although still not great, which is why Plymouth Plantation was eclipsed by the better-funded nearby Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded eight years later). New England, incidentally, was never the Pilgrims’ destination; they were aiming for the Hudson River and missed.

But you asked about Plymouth Rock. On arriving in Plymouth, it’s doubtful the Pilgrims scrambled atop any kind of rock. Contemporary accounts mention no rock. The rock stamped “1620” that today lies below a canopy built by McKim, Mead, and White has been moved around quite a bit over the years. It is, visitors to the site never fail to notice, ridiculously small.

Why did they have those hats with buckles on them?

They didn’t. That was a fashion adopted later by English Puritans.

Did they call themselves Pilgrims?

No. That designation came much later, after they were all dead. They called themselves Separatists, because they rejected the Church of England as insufficiently different from Roman Catholicism.

Was the first Thanksgiving about giving thanks?

Not exactly. It was a harvest celebration. No doubt the Pilgrims expressed thanks that they—well, half of them, anyway—survived their first winter in the New World. They were, after all, very devout. But Thanksgiving ceremonies, as practiced by the Separatists and other Protestants, were typically rituals of fasting, not eating, so nobody called it a Thanksgiving ceremony. At a Thanksgiving ceremony you didn’t eat.

Did the Pilgrims consider it a big deal?

Not enough for Plymouth Plantation Governor William Bradford to mention it in Of Plymouth Plantation, the most authoritative text. What little we know comes from a December 1621 letter by one Edward Winslow, who was the Pilgrims’ chief liaison with the crown and all-around diplomat. Here’s what Winslow said:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruits of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl, as with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.

To summarize: There was Pilgrim rejoicing, there was some Pilgrim shooting of fowl (more likely waterfowl than turkeys), and there was some celebratory Pilgrim shooting of muskets. This alarmed the nearby Wampanoag tribe, which had made a peace treaty with the Pilgrims against their common enemy, the Narragansett tribe to the south. The Wampanoag took the gunfire to mean the Pilgrims were under attack. When they found out they weren’t, they stayed for dinner, contributing three deer and staying three days, which to this day is the recommended maximum to stay with anybody.

Why did the Wampanoag want to make peace with the Pilgrims?

It was entirely strategic. They were well familiar with the destruction of which Europeans were capable, because many had drifted down from Newfoundland, where English ships travelled regularly to fish. The Pilgrims, they figured, were relatively harmless because they had children with them; because they only barely made it through the winter; and because, as Europeans went, they were relatively peaceable. But the Pilgrims had guns, which the Wampanoag figured would come in handy if their enemy the Narragansett came after them.

Also the Wampanoag’s number had been diminished 80 or 90 percent by disease, mostly through exposure to Europeans, so they were feeling a bit vulnerable.

Oh, right, the Native Americans didn’t have immunity against European diseases. What did the Europeans make of that?

They thought it was God’s will! John “City on a Hill” Winthrop, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, did not flinch from asking the question everybody asks today: “What warrant have we to take that land which is and hathe been of long time possessed by other sonnes of Adam?” Partly, Winthrop answered, because Native Americans “ruleth over many lands without title or property,” which wasn’t precisely true, but never mind. More appallingly, he wrote: “God hath consumed the natives with a miraculous plague, where by a great parte of the Country is left voyde of Inhabitantes.”

He wants us to take it!

Did peace last between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag?

What do you think?

The Pilgrims and other New England colonists violated the terms of various treaties again and again, and eventually Massasoit’s son, nicknamed King Philip, had enough. In 1675 he joined forces with the Narragansett and other nearby tribes and declared war. The war, called King Philip’s War, lasted three years. It was very bloody and economically ruinous for the colonists, but eventually the colonists prevailed. They mounted King Philip’s severed head on a pike in Plymouth Plantation, which is not a very happy end to the story of the first Thanksgiving.

Did the Native Americans teach the Pilgrims to grow corn by planting the seed atop a fish that served as fertilizer?

That is the only thing they told me about Thanksgiving in the third grade that turned out not to be bullshit. Yes, they did!

Was the first Thanksgiving the start of the Christmas season, like it is today?

Here’s the best thing I know about the Pilgrims. They thought Christmas and Easter were so much popery and therefore didn’t celebrate either.

Didn't want to rain on your parade, but there are a lot of beliefs out there that are not true. You should read "In Small Things Forgotten" -- a quick read-- by James Deetz for some interesting myths and the realities as discovered by archeologists.....

I am afraid that your only truth is only partly true. The Indians were not farmers and in fact they learned to put a fish in the soil from the Dutch.... Check it out... But I loved this....gloria