Dump Cuban

Kamala Harris's campaign proxy is on a media blitz to persuade rich people she isn't serious about addressing economic inequality. That isn't helpful.

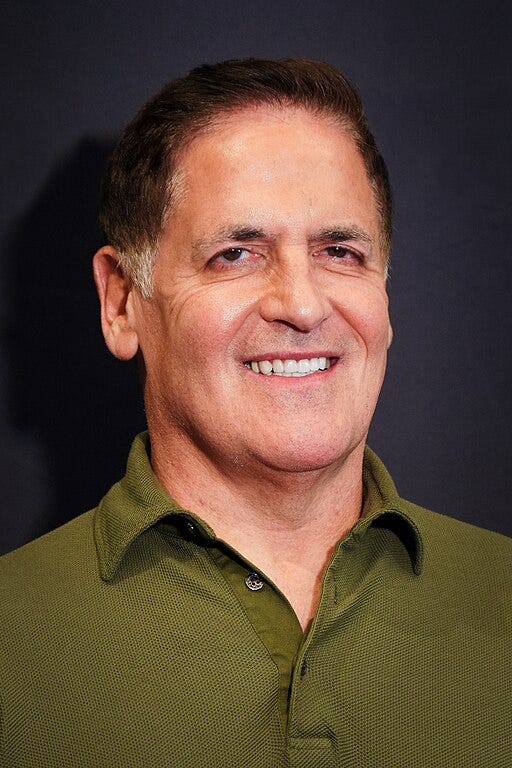

Call me old fashioned, but Mark Cuban is not my ideal of a campaign proxy for Kamala Harris.

If beating an insider-trading rap were a qualification to become chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, then the billionaire financier, Shark Tank cast member, and ubiquitous Kamala Harris campaign proxy Mark Cuban, who offers himself up as a potential choice (“Put my name in for the SEC, it needs to change”) would be a shoo-in.

In November 2008 the SEC, then under the chairmanship of the industry-friendly former Republican congressman Christopher Cox, accused Mark Cuban of committing securities fraud when he sold 600,000 shares in the search engine company Mamma.com prior to a public stock offering, thereby avoiding losses in excess of $750,000, according to the SEC charging document.

According to the SEC, Cuban, who held the largest (6.3 percent) stake in the company, knew the shares would be sold below their market price because this was a “private investment in public equity” offering, or PIPE, a type of public stock offering in which stocks typically sell at a discount. When the company’s chief executive, Guy Fauré, told Cuban of the plan by phone, informing him up front that this information was confidential, Cuban got angry and said he didn’t like PIPEs because they diluted the value of existing stock. “Well, now I’m screwed. I can’t sell,” Cuban said, according to the SEC. After receiving further confidential information from the investment bank in charge of the PIPE, according to the SEC, Cuban phoned his broker and told him to sell his entire stake. Cuban later stated publicly that he sold his shares because he knew Mamma.com was conducting a PIPE.

Cuban’s case didn’t come to trial until September 2013. After three weeks of testimony the jury found Cuban not guilty. An expert witness testifying on Cuban’s behalf apparently persuaded the jury that the impending PIPE was publicly known (even though pretty clearly it was not previously known to Cuban, the company’s largest stockholder). In addition, Fauré, who was logically the prosecution’s star witness, did not want to testify and was able to avoid doing so because he was Canadian. The prosecution also blundered in trying the case in Dallas, where Cuban was the popular owner of the local professional basketball team, the Mavericks. (I rely here on an analysis by another one of Cuban’s expert witnesses, Marc I. Steinberg, professor of law at Southern Methodist University.)

I don’t pretend to understand the technical issues that arose in this prosecution (which Steinberg also discusses). But the facts of this case are not, I think, the type of experience we’re looking for in an SEC chair. Nor do they make Cuban the person to whom I’d turn for an objective assessment of current SEC chair Gary Gensler, of whom Cuban is fiercely critical (as he also is of Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan). Nor do they make Cuban a suitable campaign proxy for Harris, who is campaigning partly on the strength of her past experience as a prosecutor.

But none of these objections constitute the main complaint I offer about Cuban in my latest New Republic piece, which is that Cuban is working hard to persuade his fellow plutocrats that Harris isn’t serious about addressing economic inequality, and that he’s doing this job altogether too well. That is not the message that the working class, whom Harris is struggling to reach—and without whom she can’t win—particularly wants to hear. You can read my piece here.