Does the Biden administration anticipate strong economic growth, or weak economic growth?

Depends on who you ask.

Behold today’s dueling front-page headlines in the New York Times and the Washington Post. I fell a bit behind in my news consumption these past few days and was counting on today’s print newspapers to catch me up. Imagine my confusion when I saw this. Never mind what direction the economy is taking; I expect there to be disagreement about that. But does the Biden administration anticipate a strong economy or a weak one? According to America’s twin newspapers of record, the answer is “yes.”

The differing headlines (which I reproduce in homage to my friend and erstwhile boss Mike Kinsley, who made this sort of zany discrepancy a running feature when he was editor of the New Republic) reflect disagreement not so much about the economic assumptions underlying Biden’s budget as about their significance. Both newspapers agree that that Biden’s budget assumes that economic growth will be strong in 2021 and 2022. Where the newspapers differ is in the relative interest we should have in the Biden administration’s short-term versus longer-term projections, and in whether any of these projections have much value.

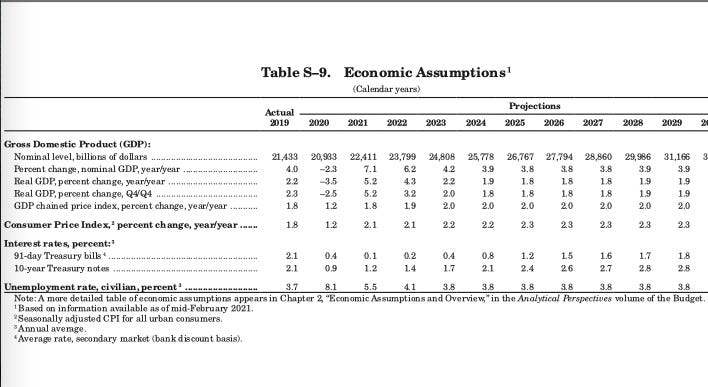

Neil Irwin of the New York Times, who writes for the Times’s nerdy “Upshot” department, says the strong growth in 2021 and 2022 still won’t “return the economy to its pre-pandemic trend line,” i.e., the slow-starting recovery from the 2007-2009 Great Recession that eventually grew strong under President Barack Obama and remained strong under President Donald Trump. From 2010 to 2019 the average annual GDP growth rate, Irwin reports, was 2.3 percent. But after a post-pandemic spurt this year and next, the Biden administration projects GDP growth will slow to 2 percent and then 1.8 percent. Irwin’s subtext here is that Biden’s $6 trillion budget won’t overheat the economy. Wages will go up, but inflation won’t get out of control.

Jeff Stein of the Washington Post is the White House economics reporter, which means his orientation is somewhat less nerdy and more political than Irwin’s. Stein reports that the Biden administration projects more than 5 percent growth in 2021 and 4.3 percent growth in 2022, and that “the economy has not grown at a rate faster than 4 percent in more than 20 years.” What’s more, Stein writes, White House officials say these estimates may be too conservative, given that we don’t yet known the full extent of the economic stimulus Biden has in mind.

Irwin sees Biden’s projected growth for the next two years as so flukey that he doesn’t bother to share the specific growth numbers, 5 percent and 4.3 percent. Nor does he appear to see any point in comparing these projections with GDP growth during the tech boom of the late 1990s. The whole country has been shut down for more than a year! Of course growth will be big this year and next!

Stein judges the significance of the Biden administration’s economic forecast to reside mainly in how it reflects its thinking about the midterms. The forecasts “would set the table for a vibrant economy just ahead of the 2020 midterm elections,” Stein writes, “possibly bolstering Democrats’ shot at maintaining control of Congress despite tough odds.” Stein goes on to discuss the midterm stakes at some length. Irwin mentions the midterms only in passing; he’s more interested in how the economy will perform after that.

Stein suggests that trying to figure out how the economy will perform even over the next two years, much less the next five, is a mug’s game. He pays absolutely no attention to administration projections after 2022. “Upbeat economic projections are common in White House budget proposals,” he writes, “but economists believe forecasting the next few years is difficult.” Stein plays up the risk of inflation a bit more than Irwin, though mainly as a GOP talking point, because that’s fairly un-knowable, too.

Usually when I encounter two differing approaches like these, I give the tie vote to my onetime employer, the Wall Street Journal, which really does cover economics awfully well. The Washington news editor, Henry Oden, told me when I first came to work there in 1990 that the Journal couldn’t afford to play this bullshit lazy he-said, she-said game that the Times and the Post got away with because Journal readers had money riding on what was actually true. (Henry was one of those astonishing people who knew everything not only about your beat and everybody else’s beat but also about every other aspect of life, such as how to bleed your radiators. To this day I would never consider doing anything that Henry recommends against.)

But the Journal failed me in this instance. It didn’t bother breaking out any piece at all about Biden’s economic projections, perhaps because it agreed with the Post’s Stein that these are more plausibly political rather than economic documents. Indeed, the Journal cared so little that in its main budget story it misreported the Biden administration’s growth projection for 2022 as 3.2 percent rather than 4.3 percent, using the projected change in fourth quarter growth rather than the projected year-to-year change (see below). In my day, an error like that would have had Washington bureau chief Al Hunt baying for blood. Newspaper editors aren’t permitted to scream and yell anymore, and perhaps this is what we can expect as a result. Harrumph.

Update, June 1: This last paragraph may be unfair to the Journal. See reader comment below from David Wessel.

Without commenting on the substance of Tim's critique of the WSJ, it's not correct to say that the WSJ used the 4th quarter growth number. The budget shows -- as it always does -- an annual average (2022/2021) and 4th quarter over 4th quarter (which shows you what the economy grows in 2022 independent of how fast or slow it grew the previously year) Either is correct as long as it is labeled and one doesn't mix the comparisons.