Cybercurrency, Philanthropy, Speciesism, Bestiality, and Pissed-off Grad Students

I think that covers everything discussed below.

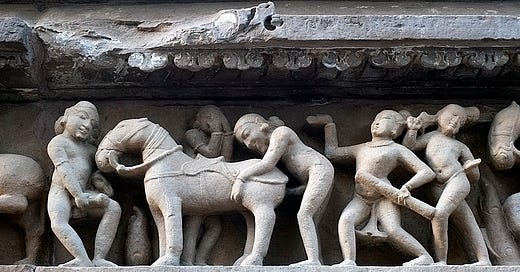

Naughty frieze at Lakshmana Temple in Khajuraho, India, 10th century AD.

Hollis Robbins is school of humanities dean at the University of Utah, a scholar of 19th century American literature, and a social-media wit, which is mostly how I know her. She’s one of those people who has something interesting to say on just about every topic, and I tried a couple of times, unsuccessfully, to get her to write for Backbencher back when it aspired vaguely to transform into a general-interest web magazine. (Robbins was amenable but, in those two instances, too busy.) I mention Dean Robbins because she shared this morning, in response to my latest New Republic piece, the following withering definition of effective altruism: “Instead of giving to soup kitchens, give to develop this app to rate the effectiveness of soup kitchens.”

Effective altruism is a philanthropic movement bankrolled largely by Sam Bankman-Fried, who’s a bit strapped for cash since the collapse of his cybercurrency firm FTX, and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. In my New Republic piece I suggest that effective altruism, which has won favor among rich young millennial and Gen Z cybernerds, is distinguished principally by the balletic grace with which it tiptoes past any topics that might upset the plutocracy. It’s not clear it will survive Bankman-Fried’s downfall. You can read my story here.

The effective altruism movement derives inspiration from a 1972 essay by Peter Singer against which I have no particular objection, which is unusual for me. In 1982 I wrote disapprovingly about Singer’s book Animal Liberation in my first-ever New Republic cover story, which was a defense of vivisection. The piece overstated its case in a somewhat juvenile manner (the author was 24), and it included an un-ironic reference to yellow rain that’s aged very badly, but 40 years later I still think my argument was basically right. It received the most voluminous hostile response of any story I’ve ever written.

My next virtual encounter with Singer (we’ve never actually communicated) was after he wrote an essay defending sexual congress between human beings and animals (“Heavy Petting”). In Slate, I answered (“The Bestiality Perplex,” April 2001) that Singer gave short shrift to the principle of consent and, in the unlikely event one could ever get past the language barrier, the question of whether animals would be qualified to give consent. My Slate colleague, Will Saletan, summarized this argument as “Neigh means nay,” and a few days later contributed a more elegant and philosophically rigorous essay of his own (“Shag the Dog”). Yes, Slate published two pieces making essentially the same argument against bestiality (proponents prefer the term “zoophilia”) within the span of a single week. Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive.

My next intersection with Singer was my favorable Slate writeup in February 2004 of his book The President of Good and Evil, which took George W. Bush to task for being a fair-weather federalist/judicial restraint advocate on the subject of abortion. Low-hanging fruit, but Singer plucked it well, and the topic is made newly relevant, alas, by Dobbs v. Jackson.

Please also consider reading my Monday New Republic piece defending the graduate-student strike at the University of California’s ten campuses. The embourgeoisement of the American labor movement, I argue, is very much a good thing. You can read it here.